Fighting Tigers

In spite of increasing anxiety, the outbreak of war did not immediately change student life at Clemson. It was true that, on December 20, 1941, Congress lowered the draft age to twenty (Reel 288). Enemy advances in both Europe and the Pacific in the summer of 1942 forced Congress to lower the draft age again, this time to eighteen. Yet since actual induction, training, and service did not immediately include males aged eighteen and nineteen, many Clemson men were able to continue their college studies until November 13, 1942 (Reel 305). By 1943-1944, however, the draft had taken its toll. Student enrollment fell to 752, the lowest number since 1920–21 and the highest it would be for the rest of the war (Reel 305-306).

Soon Clemson men found themselves scattered in battlefields across the globe, from England to North Africa to the Philippines. By early 1943, there were 3,448 Clemson men in uniform, second only to West Point and Texax A&M. This number would increase to 6,475 by the end of the war (Reel 307). The majority of Clemson men served in the Army or the Army Air Force, as the below table for the Class of 1939 shows.

| Branch | Number | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Army | 202 | 52.5 |

| Army Air Force | 75 | 19.6 |

| Navy | 24 | 6.2 |

| Marines | 3 | 0.7 |

| Home Service | 20 | 5.3 |

| Non service | 61 | 15.7 |

| Totals | 385 | 100.0 |

Table adapted from Lawrence Korth, "The Clemson Class of 1939" (2012), 46. All Theses. 1534. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses/1534. See Sources.

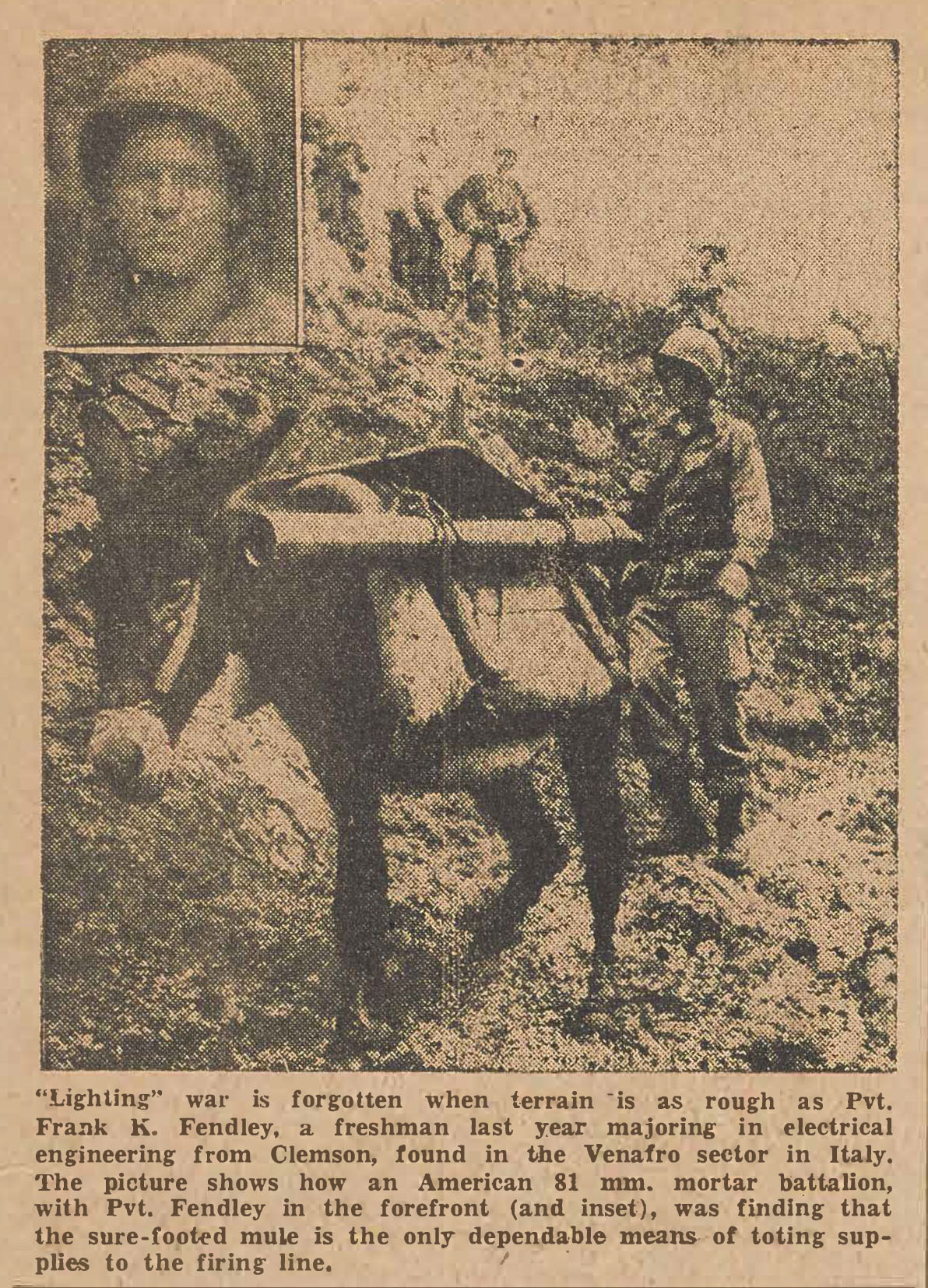

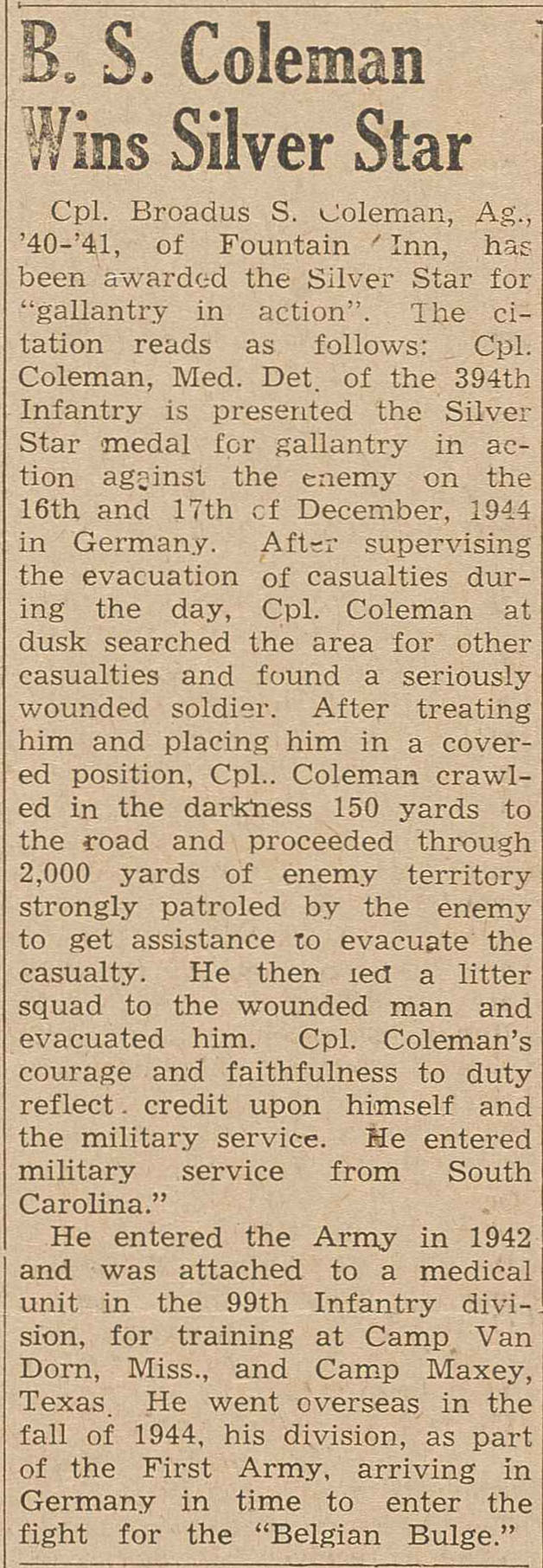

Throughout the war, The Tiger featured stories of Clemson men who had distinguished themselves in battle, sometimes at the cost of their own lives, as well as those who were wounded, missing, or prisoners of war (POWs). In addition, beginning in fall 1942, The Tiger included a section entitled “As We See It,” which printed letters received by P.B. Holtzendorff, general secretary of the YMCA, from Clemson servicemen. Later in the war, The Tiger also had sections called "People at Home and Abroad" and "So they say...", which featured news of Clemson servicemen both overseas and in the States and the men's own words from letters, articles, and interviews.

We know about the war experiences of many Clemson men only from articles in The Tiger, but a few, such as Manny Lawton and William Cline, have left behind more substantial records.

Manny Lawton

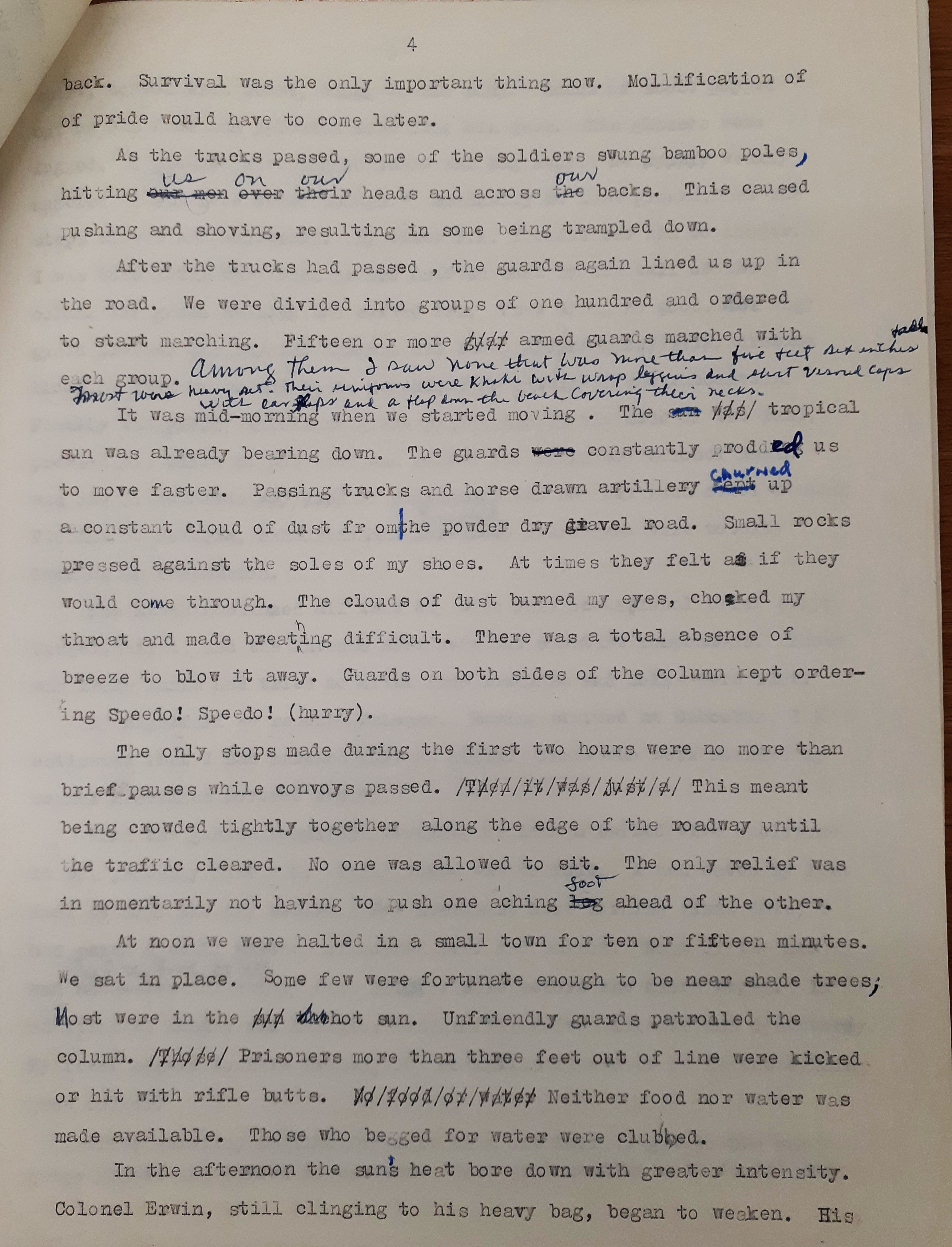

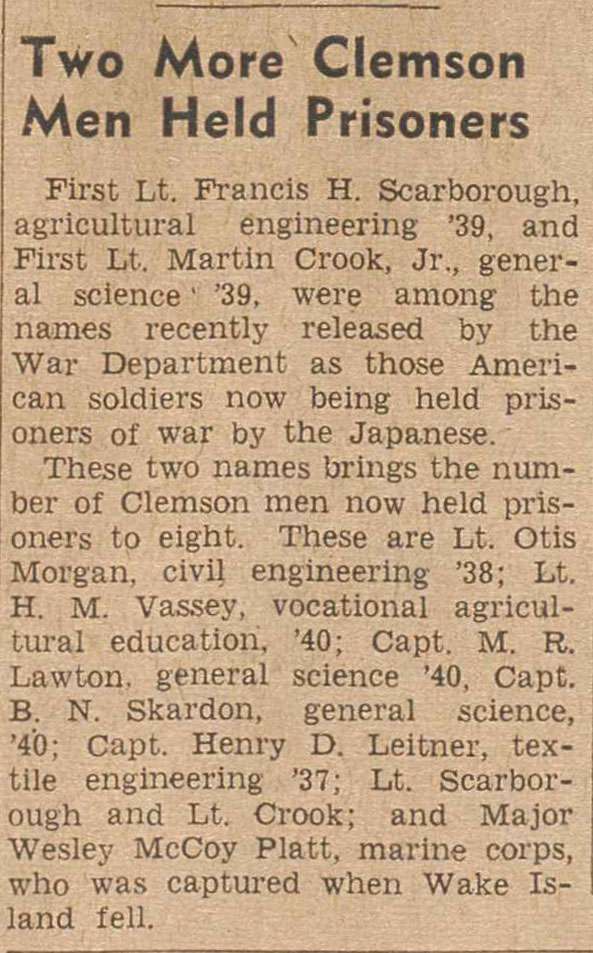

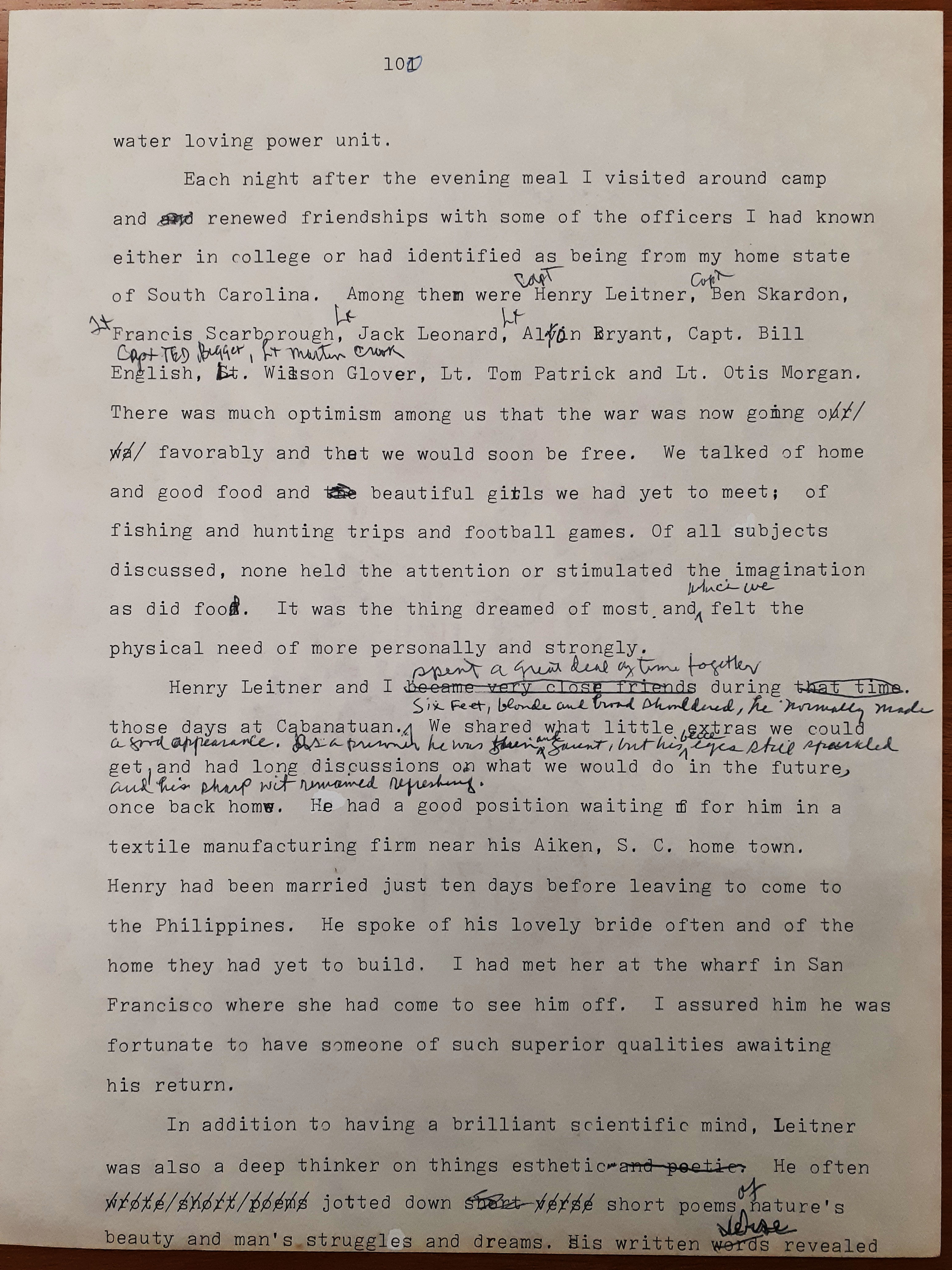

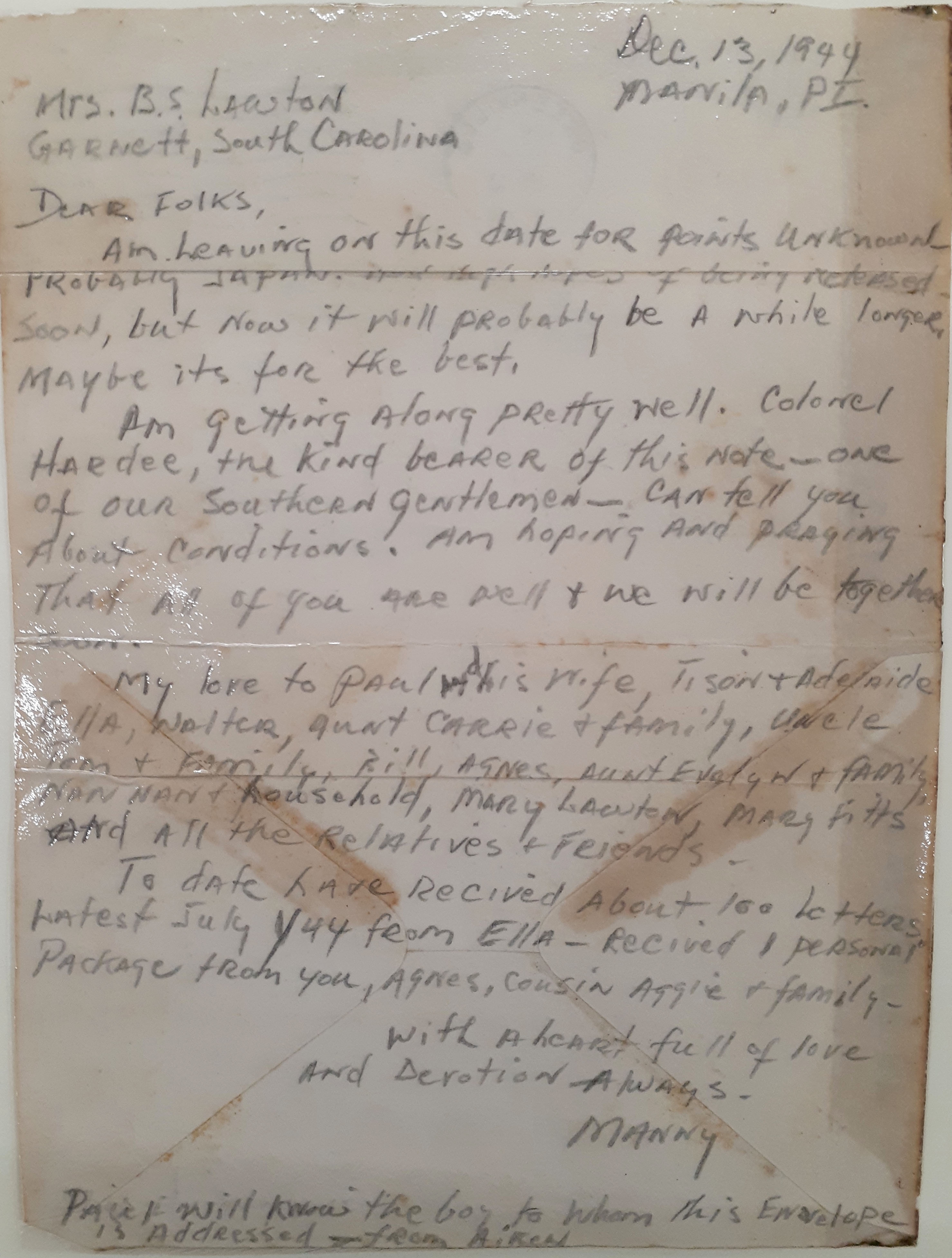

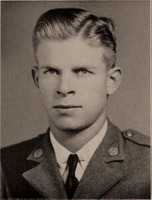

Capt. Marion “Manny” Lawton, a graduate of the Class of 1940, served as an advisor to the Philippine Army’s First Battalion. He was one of 24,000 Americans helping to build the new Philippine National Army to fight the Japanese (Reel 298-299). On April 3, 1942, the Japanese attacked Bataan province. Without supplies or reinforcements, the small army held out until April 9, when they had to surrender unconditionally (Lawton 5-15). About 64,000 Filipinos and 12,000 Americans, including Lawton, were taken prisoner (Reel 303-304). After stripping them of all valuables, the Japanese forced the prisoners to march to a prison camp. The prisoners had to walk about twenty-five miles a day, in the scorching heat, with minimal food and water and few medical supplies, while the Japanese guards beat and taunted them. The healthier prisoners carried those who were too sick and weak (Lawton 15-24). By the time they reached the prison camp seven weeks later, around 3,000 prisoners had perished (Lawton 31). The Japanese later moved Lawton to another camp, where he found fellow Clemson graduates Henry Leitner, Otis Morgan, Ben Skardon, Bill English, Francis Scarborough, and Martin Crook (Lawton 106). Thousands of prisoners died in the horrific conditions of the Japanese camps. Lawton suffered from malaria, beriberi, and other illnesses.

Years passed. In December 1944, as American forces drew closer, the Japanese moved Lawton and the other prisoners to Manila and loaded them into the dark, suffocating hulls of “hell ships” for evacuation to Japan (Lawton 153). American planes attacked the unmarked ships, not realizing that they carried prisoners. Otis Morgan was killed in one of these attacks (Lawton 194). Hundreds of prisoners died in the bombings, while others succumbed to starvation, dehydration, cold, and illnesses such as dysentery and pneumonia. Their ship arrived in Japan with only 400 survivors out of about 1,600 (Lawton 214). Leitner soon died from pneumonia, while Lawton survived until the Japanese surrender. Skardon was liberated from a Japanese camp by the Soviet Red Army (Reel 304). Lawton later recounted his experiences in Japanese captivity in his memoir Some Survived, of which a few annotated drafts form part of this collection.

William Cline

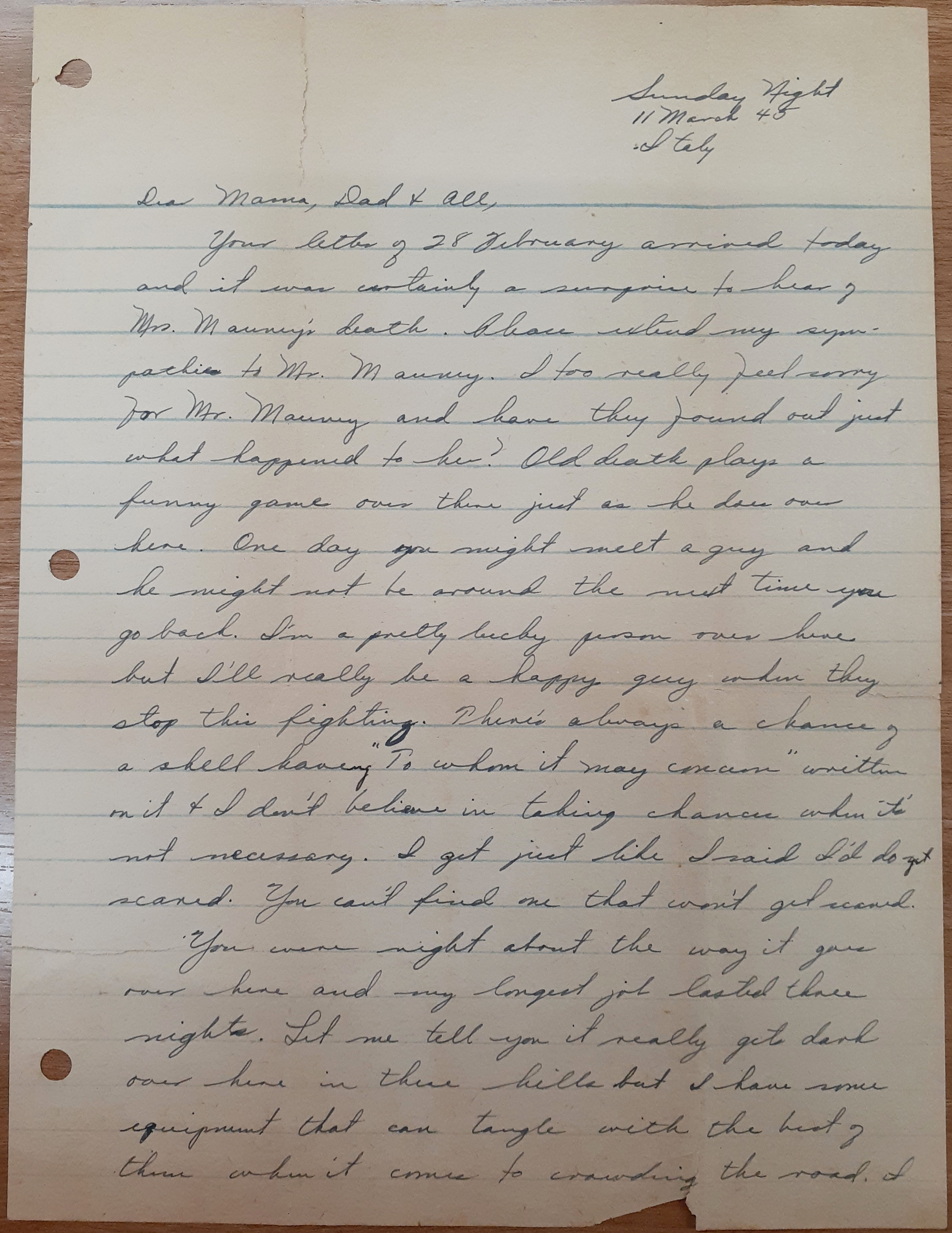

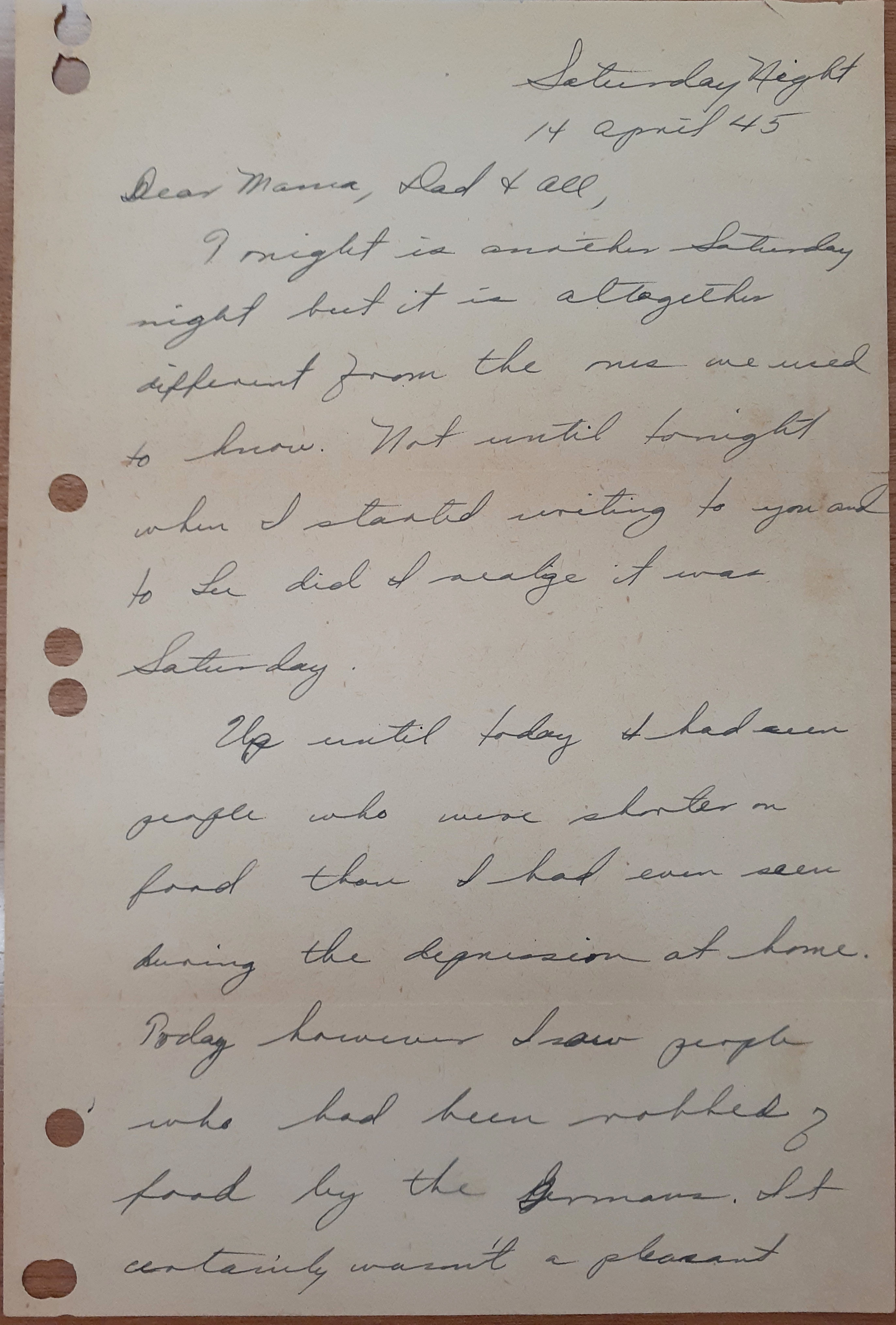

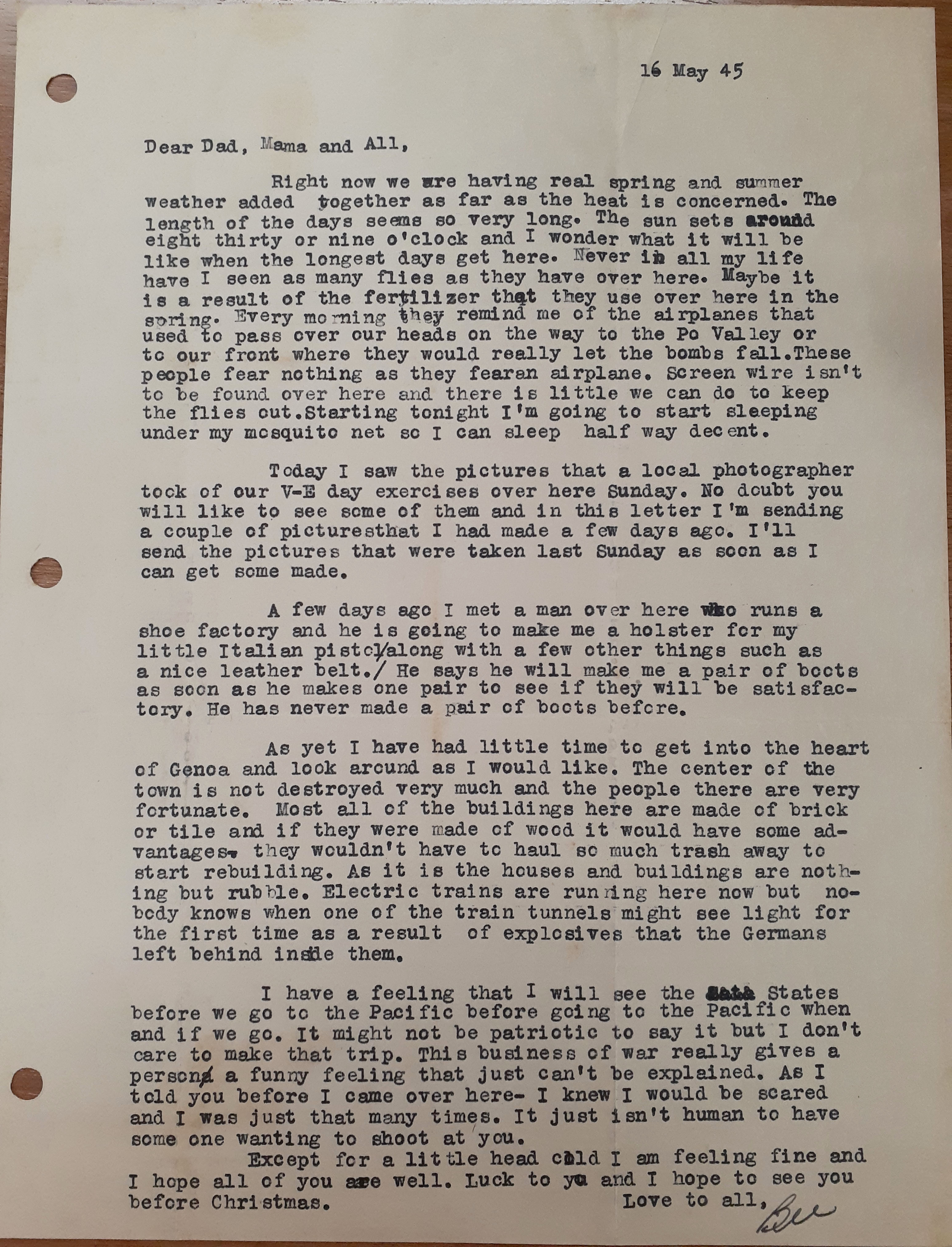

Capt. William Cline, a graduate of the Class of 1941, was an officer in the 758th Tank Battalion, an all-black unit that was part of the 92nd “Buffalo” Infantry Division. The 758th was one of three segregated tank battalions in World War II. In this battalion, the combat units were led by black company commanders, while the service and administrative units were commanded by white officers. Cline was in charge of the 758th Service Company, which recovered damaged vehicles and provided maintenance and repairs (Scar).

After completing his armored training at Fort Knox, Cline was deployed to Italy in November 1944. This was during the Germans’ last desperate stand in Italy. The Allied invasion of Sicily in July 1943 had led to the collapse of the Fascist Italian regime and the fall of Mussolini. However, German forces soon took control of northern and central Italy and helped Mussolini to establish a collaborationist puppet state. The Allies invaded Italy in September and the fighting was fierce. Cline’s battalion used M5 light tanks against the Nazis and the Fascists in northern Italy, fighting their way from the beaches of the Ligurian Sea through the Po Valley and into the rugged Apennine Mountains, where they helped breach the Gothic Line--the Germans’ last major line of defense in Italy (Wilson).

After Germany surrendered in May 1945, there was the possibility that soldiers in the European theater would be sent to the Pacific to fight the Japanese, but Cline remained with the occupation forces in Italy until his discharge at the end of 1945. Cline carried a small Leica camera with him and snapped photos of destroyed tanks, the soldiers in his platoon, and places of interest during his sightseeing trips. He also wrote letters to his parents back home in Newton, North Carolina, describing his experiences as a tank man and a white officer in a segregated unit.