Turning Point

On the afternoon of December 7, 1941, Clemson cadets and faculty "had settled in after church and their Sunday dinners for the remainder of the 'day of rest and gladness'" (Reel 300). Some were listening to music on the radio, when suddenly a newscaster broke in, "We interrupt this program to bring you this news flash. The Imperial Japanese Air Force has bombed the United States Naval Base at Pearl Harbor..." Stunned, listeners thought that perhaps the attack had been made by "a renegade group within the Japanese military" (Reel 300).

By the next morning, however, Americans knew the truth. On the radio, they heard President Roosevelt announce in a joint session of Congress, "Yesterday, December 7, 1941, a date which will live in infamy, the United States of America was suddenly and deliberately attacked by naval and air forces of the Empire of Japan." "Very many American lives have been lost," he said. "In addition, American ships have been reported torpedoed on the high seas between San Francisco and Honolulu." In fact, 2,403 Americans had been killed and 1,178 wounded. Most of America’s Pacific fleet was either destroyed or badly damaged ("Pearl Harbor Fact Sheet"). The Japanese had also attacked Malaya and Hong Kong, Guam, the Philippines, Wake Island, and Midway Island. In spite of the scale of destruction, the President assured Americans, "With confidence in our armed forces, with the unbounding determination of our people, we will gain the inevitable triumph. So help us God."

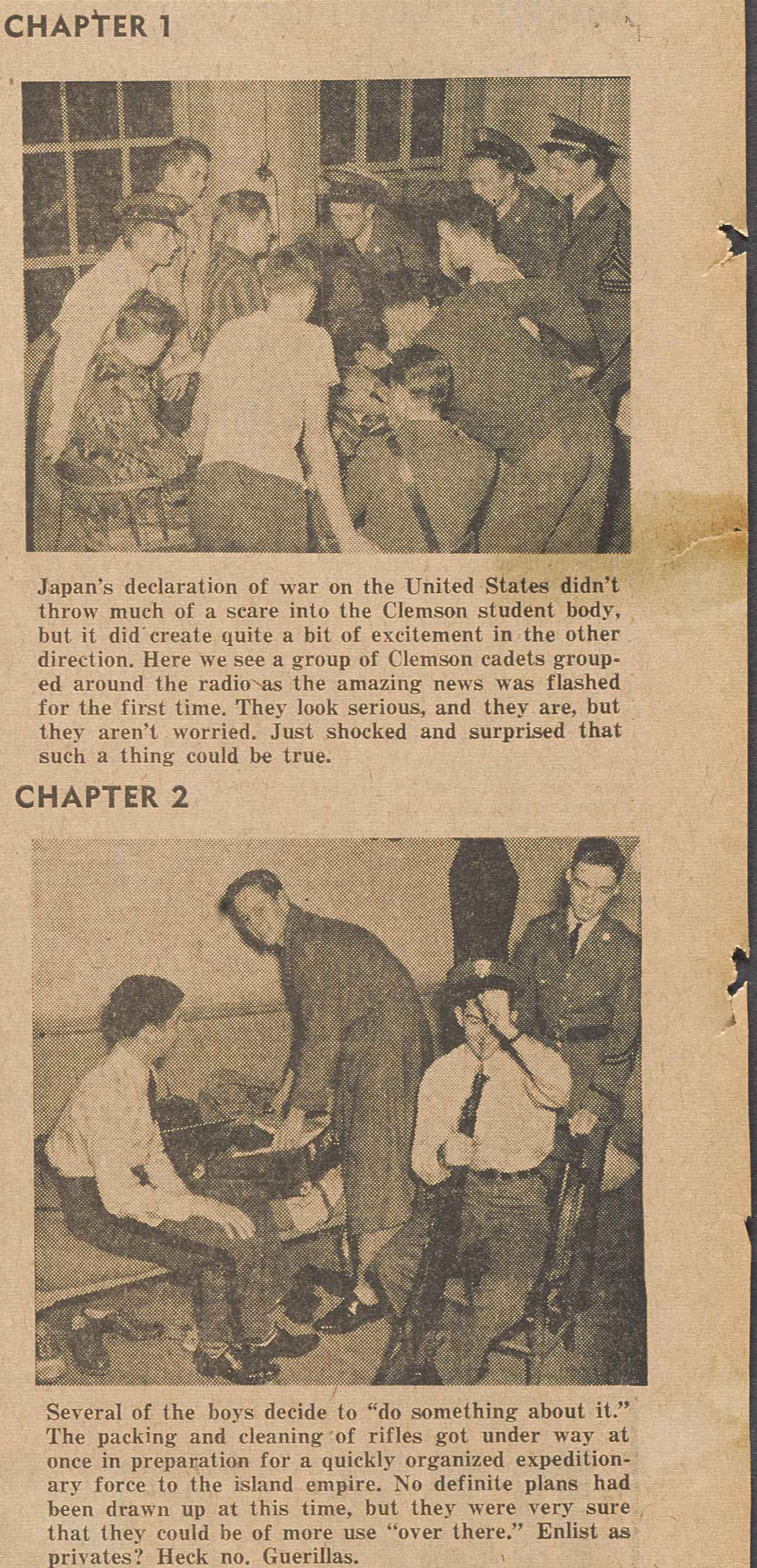

With the attack on Pearl Harbor, antiwar sentiment disappeared. The isolationists in Congress, “almost to a man,” became hawks and voted to declare war on Japan (Cardozier 3). Four days later, Germany declared war on the United States. America now found itself in the midst of a second World War. While Americans reacted “with a mixture of anger and hysteria,” the mood was “somber” on college campuses (Cardozier 3). Students were “confused, gloomy, and disbelieving,” as they realized that sooner or later they would be “called to military service with the specter of combat and possibly death looming in the future. Most were quiet and unsure of what to do or think…” (Cardozier 3).

At Clemson, President Robert Franklin Poole urged the cadets to “remain calm and collected” and to “work as hard as possible on your courses and prepare yourselves that you may serve your country efficiently and effectively when called.” Clemson alumnus and war correspondent Ben Robertson also told the students to “be patient and quiet. We must remember, without doubting, that the war we are now in will certainly last for a very long time, and that before it is finished the time will come for all of us to fight.” Likewise, an editorial in The Tiger cautioned students, saying that “it is just as patriotic [for cadets] to continue their normal duties until they are called, instead of rushing to the nearest recruiting office to enlist. When the time comes, Clemson men...will consider it a privilege to fight for the greatest nation in the world.”

Meanwhile, Clemson faculty charged that the Japanese lacked “honor and decency” and students called the attack, variously, “one of the most outrageous and dastardly acts that this world has experienced,” “a stab in the back,” and “a grave error.” The students expressed their willingness to fight. “I am ready to go at any time,” said Philip Sutler of Columbia, South Carolina, echoing the sentiments of many of his fellow cadets. In a show of patriotism, a group of freshmen cadets even attempted to leave campus to go fight against the Japanese.