War Clouds Coming

The tensions that had been building in Europe due to Nazi aggression finally erupted into war on September 1, 1939, when Nazi Germany invaded Poland. With their superior weapons and lightning-fast mobility, the Germans conquered the country within a month. The invasion of Poland shocked many Americans, who had hoped that Hitler would be satisfied with Czechoslovakia and Austria. Nevertheless, Poland was far away, and the United States was not involved (Cardozier 1). A few days after Poland’s surrender, France and Great Britain declared war on Germany, but there was little military action for more than seven months.

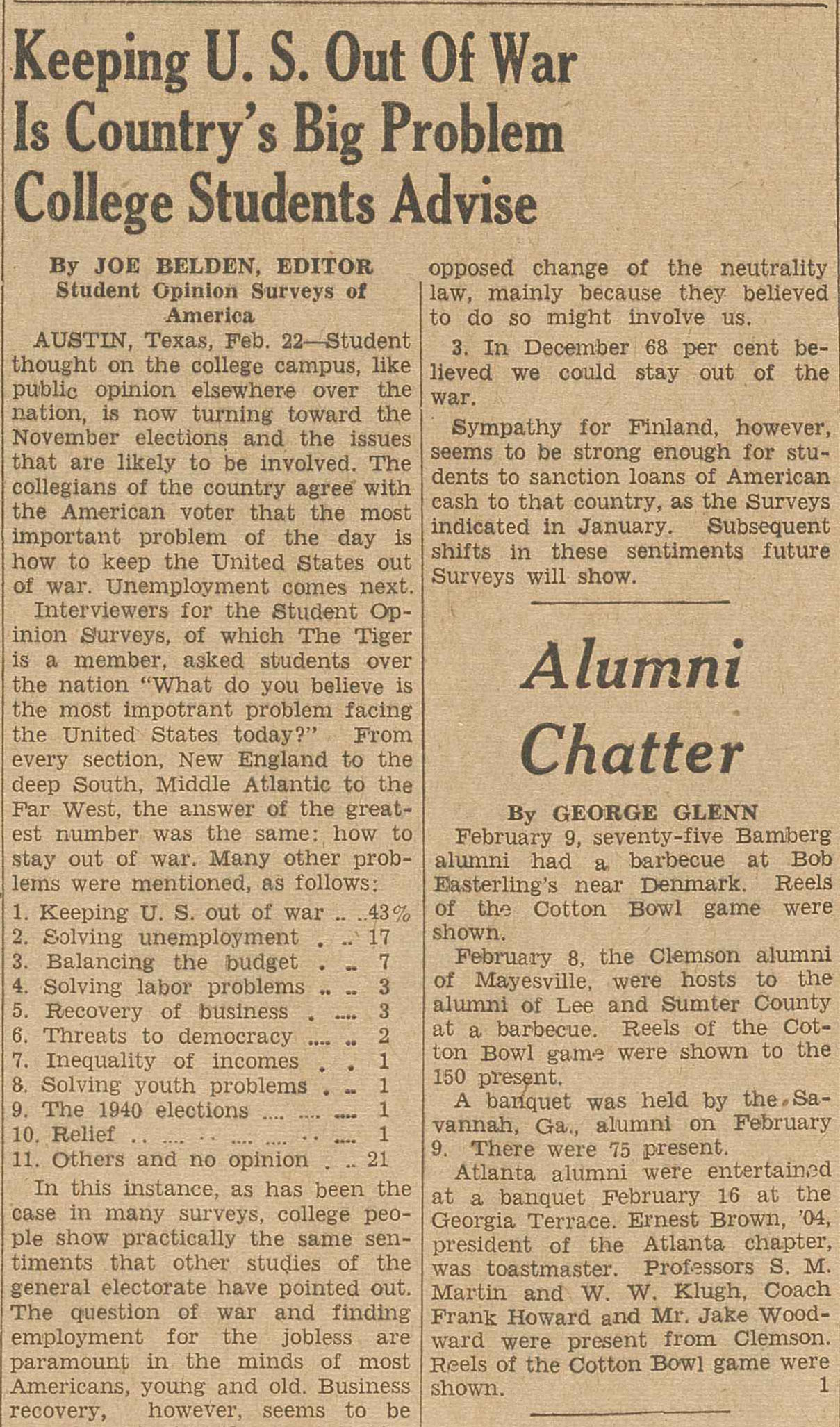

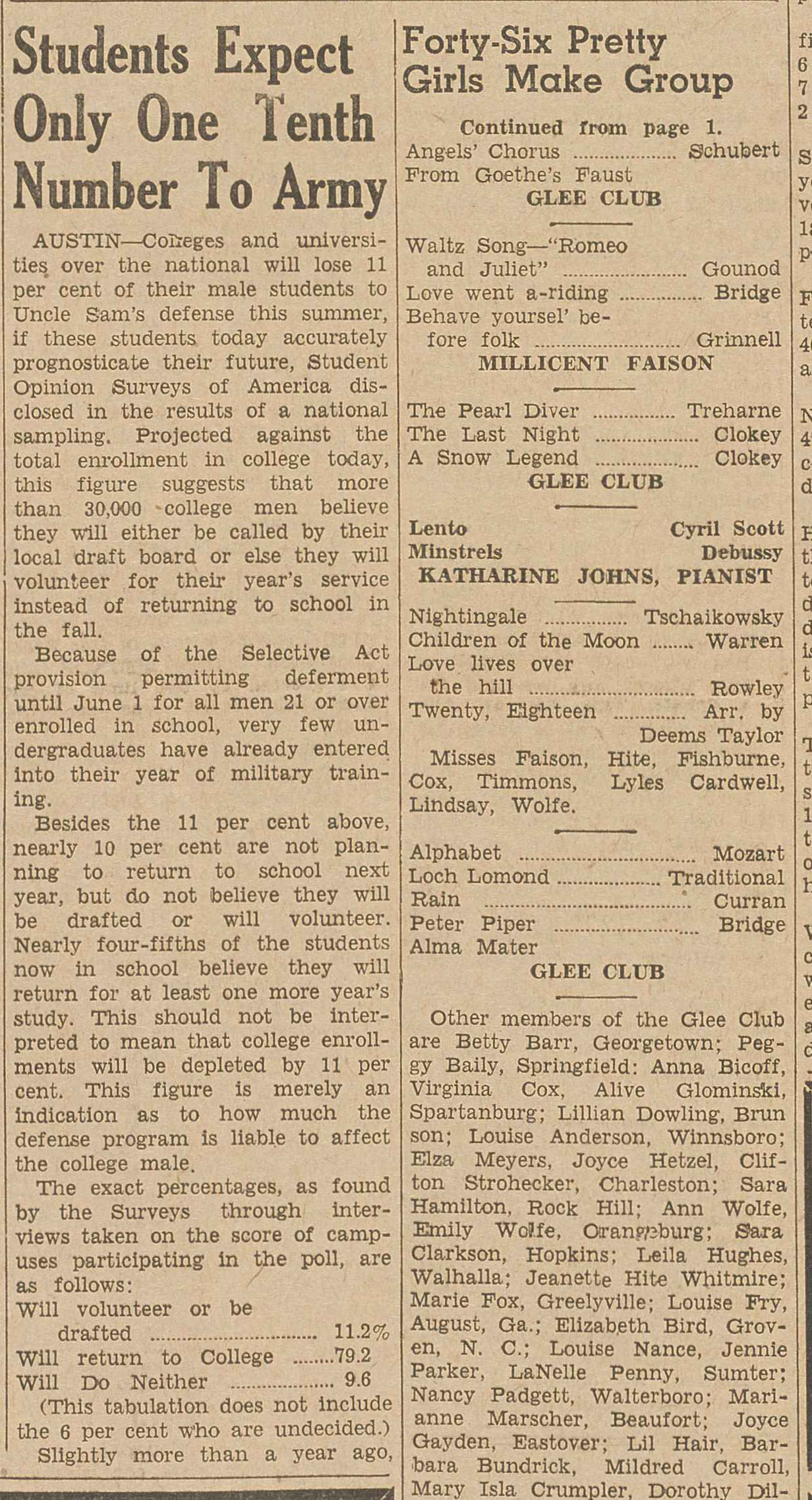

During these early years, a strong isolationism dominated American college campuses. There had been a nationwide student rally for peace every April since 1935. Some students sent petitions to President Franklin D. Roosevelt, vowing not to fight if America became involved in the war (Cardozier 2). Student newspapers around the country overwhelmingly supported the antiwar movement. The Tiger was no different. On February 23, 1940, Clemson’s student newspaper published the results of a national Student Opinion Survey, which showed that 43 percent of college students believed that keeping the United States out of war was the most important problem facing the country.

Then, on May 10, 1940, Germany invaded the Low Countries, moving into France in June. After quickly overrunning France, the Germans began their aerial and naval assault on Britain. On August 15, the German Luftwaffe started bombing British cities, ports, factories, and shipping almost every night. In a massive bombing campaign called “The Blitz,” which began on September 7, London was bombed on fifty-six consecutive days and nights. Over 40,000 British civilians were killed during the Battle of Britain (Overy clxiv).

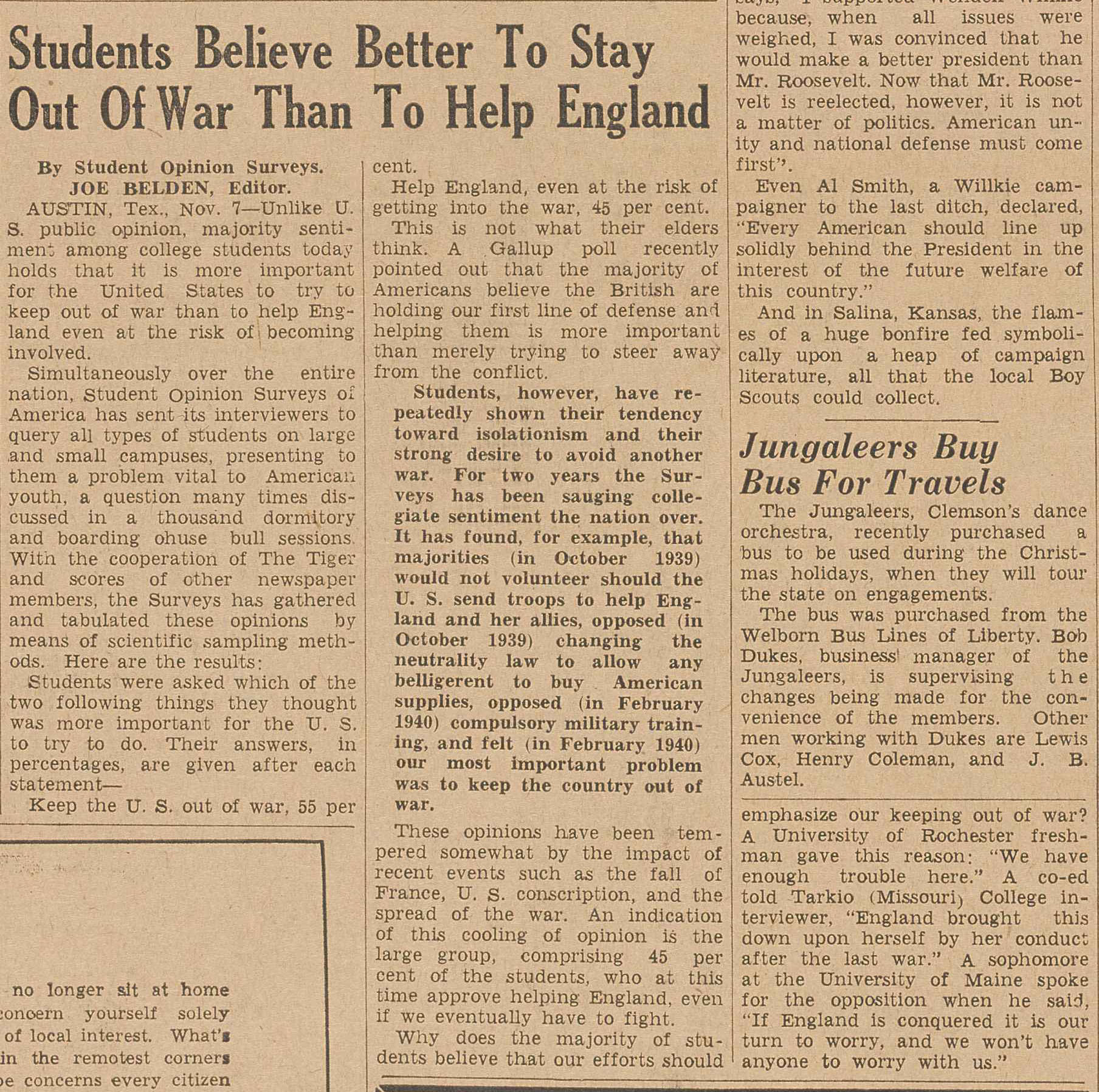

The bombing of Britain had a profound effect on Clemson students. On November 8, 1940, The Tiger published the results of another Student Opinion Survey, which showed that 55 percent of college students believed that it was more important for the U.S. to stay out of war than to help England. Nevertheless, 45 percent said that the U.S. should help England even at the risk of getting into the war. By February 1941, Clemson cadets were willing to participate in a program by the British War Relief Society to raise funds for the purchase of a rolling kitchen to feed the homeless in England. The cadets had contributed $150 by March. In May the entire senior class voted unanimously to donate their uniforms (each valued at $125) to Bundles for Britain at the end of the school year. Also that spring, Clemson students expressed their strong disagreement with the views of the short-lived American Youth Congress, whose members called for a strike against war and a stop to all American aid to Britain.

The prospect of military service became increasingly likely for Clemson cadets when Congress passed the Selective Service Act in August 1940. It was the first peacetime conscription in the history of the United States. The minimum age for registration was 21 and college men were allowed to defer their enlistment for one year. On October 16, 1940, more than three hundred Clemson students registered for the draft; they would be eligible for enlistment after July 1, 1941. Most American college men, however, expected to return to school in Fall 1941, according to a Student Opinion Survey. Thinking back to that summer, members of the Class of 1941 later recalled, “We received our diplomas on one side of the stage and military orders on the other, wondering what was in store for us” (quoted in Reel 288).