1920 Walkout

The troubles at Clemson College began on Sunday, March 7, 1920 in the mess hall. Students were known to complain about the quality and lack of variety of the food. The student body collectively referred to the frequent offering of cornbread, grits, and cane syrup as "zip" because "It zips right through you!" (Reel 223). Additionally, it was customary at the start of each term for freshman cadets to be hired as waiters in the campus mess hall. Although financially compensated, these waiters were often subjected to harassment by older cadets. On March 7, facing a shortage of waiters due to influenza, Commandant Lt. Col. James M. Cummins issued General Order No. 133 stating that six cadets would be detailed for mess hall duty--without compensation--until further notice. Irked by the prospect of a thankless task with no financial compensation several cadets refused the order, received demerits, and were placed on arrest.

Members of the Senior Class Committee met with President Walter M. Riggs to raise concerns over the Commandant's order and the rising tensions. The order was rescinded the following day; however, members of the freshman and sophomore classes had already coalesced around their shared complaints. According to Commandant Cummins and President Riggs, many students were seen sporting red badges, and Cadet Thomas Crosland was punished for allegedly shouting Bolshevik slogans on campus. Tempers festered for a few days with many cadets advocating for the commutation of recent punishments. President Riggs, although happy to hear out the grievances of the students, appeared unable to assuage the tension. On Wednesday, March 10, the freshman and sophomore classes met on Riggs Athletic Field , spoke once more with President Riggs, and ultimately decided to leave campus in protest.

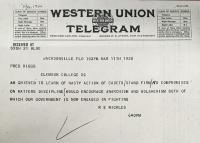

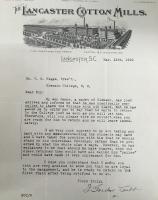

President Riggs wrote a report to the Board of Trustees, and he notified them that his resignation was "perpetually before them" should they have doubts on his leadership. His resignation offer was firmly rejected. As cadets returned to their homes, they were met by widespread condemnation for their actions. By and large, parents--even those who believed that campus conditions should be improved-- were stunned that their cadet had taken such a rash action. Parents swiftly began writing President Riggs in hopes of their student being reinstated. President Riggs received a multitude of correspondence from across the country relaying support for the College and its administration in the face of "anarchism and Bolshevism." In the days following the walkout, it was unclear whether the protest had produced any productive results.