-

Speakers-unknown female family member of Mrs. Henderson's, Elsie Henderson, Audrey Lawrence

Audio Quality-Good

Location-Seneca, SC

**Note** the first 10:44 of this interview is that of an unknown female family member [possibly a niece of Mrs. Henderson's]. This individual grew up on her grandfather's farm (area was known as Moore's Farm). She makes brief comment regarding her grandfather's land and its connection to the construction of the local Southern Railroad, her father's employment as a cook with the Southern Railroad, her educational experiences, local black churches, and her admiration of the way in which the state of South Carolina handled de-segregation, specifically in regards to Clemson University.

Side 1

10:50--Elsie Henderson gives her name and address.

11:25--As a child, Mrs. Henderson attended a school near the Oakway/South Union community. She had to walk three miles to and from school everyday. She can remember having a male teacher, but doesn't provide his name. The children got an hour for lunch, and usually played baseball at recess.

13:14--She didn't attend the camp meetings held at Bethel Grove until after she was married. She can recall ministers from all around the local area attending, along with much testifying, singing, and plenty of food.

14:46--Mrs. Henderson herself was a member of a local singing convention. The event was usually held once a year during either the summer or spring. There was no preaching, just a multi-denominational gathering of local choir groups. Mrs. Henderson and her mother were a part of the WMA within their church. Her mother, in fact, was president of the group for thirty years.

18:33--Mrs. Henderson explains that when she was a child, education had to revolve around the growing season. She briefly explains the different times of the year that children of farming families generally attended school.

19:30--Mrs. Henderson describes some of her experiences picking cotton. She states that the most amount she ever was involved in picking during one day was 350 pounds. In addition, she recalls that after school as a youth, she would help do the wash for local families.

22:35--Her family raised most of its own food, including livestock. There were not many products that had to be store bought in those days.

22:57--Her mother and one sister were especially gifted with sewing. They did their own sewing and repaired their own clothes.

23:39--Slavery--her grandparents were slaves; she particularly remembers her maternal grandmother whose name was Laura Mann. She was from Hartwell, Georgia. She helped raise her grandchildren and would tell them stories of the slave days. Her grandmother had a vivid memory of when troops (not clear whether Union or Confederate) came through the area where she lived and in general were responsible for a great deal of destruction and looting.

29:57--Funerals--the main differences in the way services were held in the old days was that there were no undertakers, bodies were laid out at home on a board, and wagons were utilized for carrying coffins.

31:43--Audio ends.

Side 2

00:07--Mrs. Henderson giving an answer to a question that had been asked prior to when the recording began. The recollection is of her mother's doctor who was from Fairplay, SC.

2:49--She never traveled to Anderson or Greenville very often; virtually all her shopping was done around the Seneca area.

3:25--Most of her siblings have predeceased her. Several lived and were buried in different parts of the United States such as Cleveland, Ohio, and Seattle, Washington.

5:24--White/black relations--Mrs. Henderson always got along with whites. She can remember occasional schoolyard squabbles as a youth, because the white and black schoolhouses were close in vicinity to each other. After marrying, she lived with her husband in a mostly white neighborhood; there were no real problems.

7:50--During Christmas, her parents would prepare large meals with turkey and ham. She briefly describes the process of how both of these meats were prepared.

10:40--Mrs. Henderson looks back fondly on her life. She cherishes the memories of days in which things were homemade, and families were close-knit.

15:29--Audio ends.

-

Speakers-Montana Haynes, Yolanda Harrell

Audio-Good

Location-Seneca, SC

Cassette 1

Side 1

1:20--Mrs. Haynes gives a lengthy family history, and reflects on memories of life in Oconee County from her childhood. She gives the unique story behind her name "Montana." She has mixed ancestry on both sides of her family. Her grandfather was an "Indian" that married a woman who "...was very white." Mrs. Haynes does not make clear whether this woman was a Caucasian or mulatto. In a later interview, speculation is that her grandfather may have been of East Indian descent, not a Native American. She goes on to explain that mulattos were known as "lily whites." There was some friction between the black and mulatto communities, because mulattos "acted white," and sought to stay higher in the social order than what blacks were allowed. Her parents worked for the influential Gignilliat family of Seneca with whom they enjoyed a great relationship. Mrs. Haynes states that issues regarding slavery were never really discussed by family members. Origins of her family names during slavery were passed down, however. She briefly discusses issues regarding the various jobs that were commonly available to black individuals.

31:22--Audio ends.

Cassette 1

Side 2

00:30--Haynes continues talking about jobs before the conversation turns toward shopping practices, including which items were produced at home versus which were purchased at local stores. The family raised its own food and only had to buy staples such as sugar and coffee. She recalls picking cotton as a youth and aspects of local farming.

11:42--Mrs. Haynes discusses family members who were known for special talents. Hardships suffered by the family over the years are recalled; these were especially associated around the time of World War I when food had to be rationed, and also during the outbreak of the flu epidemic in 1917-1918.

21:50--Mrs. Haynes relates her family's involvement with the local Ebenezer Baptist Church. She explains that at one time the church had a series of "jack-leg" preachers (untrained circuit riders). She describes the churches role in the community, camp meetings, singing conventions, and sings a few lines of her favorite hymn.

31:45--Audio ends.

Cassette 2

Side 1

00:21--Aspects of local church life continue to be discussed. The notion of blacks and whites worshipping together was not completely unheard of in the old days. Groups within the church included the Men's Club, and the Women's Missionary Society. These groups helped the needy and sick. There was also a married and singles ladies club, as well as a youth club.

5:20--Education--Mrs. Haynes started school around the age of five. She initially went to Seneca Institute where she was educated one on one with no other classmates. She recalls that the teachers at the Seneca Institute were student teachers. When she later attended elementary school, she had a difficult time adjusting because she had been used to being around young people who were in their teenaged years. She recalls how many people were in a typical class, the school building, and the curriculum. There was an eight-month school year for city children. Individuals who lived in the country attended much shorter sessions on account of farm work. She re-entered Seneca Institute at grade eight. Mrs. Haynes attended Morris College in Sumter, SC. During the four years she was there, she attended the equivalent of two additional years of evening classes in order that she obtain her teaching certificate. The college atmosphere was male dominated; she was often the only woman in class. She began getting teaching experience at the age of fourteen.

31:15--Audio ends.

Cassette 2

Side 2

00:32--Aspects of education are discussed exclusively during this part of the interview. Mrs. Haynes recounts her first experiences with teaching at the age of fourteen when she taught summer courses in Central, SC. She makes comment on the general levels of education received by both her parents and grandparents. At Morris College, she felt some degree of gender discrimination prior to her first teaching experience. Mrs. Haynes then goes on to summarize her educational career and her work with Special Education. She recalls what books, magazines, and newspapers were available to the family when she was a child. She was the first person in her family to attend college and states that her first exposure to issues such as "black history" didn't occur until college.

31:00--Audio ends

Cassette 3

Side 1

00:28--Organizations that her relatives belonged to included sewing clubs where, once a month, women met in local homes to share patterns and designs and hold quilting parties. Church groups included missionary societies; her father and mother were a deacon and deaconess, respectively.

2:15--Politics--Mrs. Haynes parents were the first to vote in their family.

4:30--Slavery--Mrs. Harrell wants to know what is meant by the term "breeders" that is occasionally used to describe mixed race relationships during the slave era. Mrs. Haynes explains that the best-looking, healthiest slave women were often picked out by slave masters in order to have mulatto children. Her own ancestry included such mixed-race relationships. Some slave masters were nice to slaves, some were not--it just depended on the individual.

7:25--In her experience, white/black relations were positive. Whites were always nice to her family and she was never warned about whites nor told how to act around them.

9:40--Lynching--the only incident that she heard of was the one involving Mr. Green from Walhalla, SC.

10:09--Law enforcement was strict on blacks when she was a youth. She explains that they were not careful in those days to conduct full, proper investigations.

10:46--The marriage relationship between her parents was an equal one.

12:15--Mulattos--she explains that mulattos as well as whites discriminated against darker hued individuals. There was considerable friction between the black and mulatto community in her estimation. Many mulattos "passed for white." Mrs. Haynes states that whites couldn't always tell people's ancestry, and accepted these individuals into higher society.

17:16--She states that her grandfather was "Indian," but had very dark skin, curly hair, and spoke with a different accent. He didn't like African Americans, and married a mulatto woman who had blue eyes. The physical appearance leads the two to speculate that he may have been of East Indian descent, and not a Native American.

20:03--Her parents never took trips to Anderson, SC or Greenville, SC. There was simply no need to travel that far in those days. Mrs. Haynes herself only began visiting the two cities when she was older and had a car.

22:02--Notable local celebrations of a sort occurred whenever the circus came to town. She can remember that they would usually make camp on Oak Street in Seneca, SC.

23:24--Holidays--her family didn't celebrate July 4th or anniversaries, but did celebrate birthdays and Christmas. She can recall that the Gignilliat family always gave her family very nice gifts. Birthdays were recognized.

29:03--Her brother Napoleon was killed during World War II in Italy. He is buried in Florence, Italy.

32:22--Audio ends.

Cassette 3

Side 2

00:35--Mrs. Haynes recall that her brother was in the Third Army with General Patton.

3:25--Her father cherished gardening and landscaping.

4:24--Mrs. Haynes greatly admired the Gignilliat family for their kindness and generosity. They were proud of her accomplishments. Her mother was also an individual to be admired.

9:20--She didn't give any thought to the fact that she was black. She again credits the Gignilliat's influence and the fact that she played with white children as a youth.

12:30--Mrs. Haynes is proud of her own accomplishments and has been well pleased with life. She recalls a few of her many honors included being included in Southern Biography, received the key to the city of Easley, SC, honored by Clemson Extension, and was awarded with numerous American Legion recognitions.

21:55--Audio ends.

Montana Haynes was born on June 6, 1907 in Oconee County near Seneca, SC. She was the daughter of Will Jr. and Jennie Everheart Perry. After completing her college education, she taught Special Education in Pickens County, SC.

-

Speakers-Douglas E. Harbin, Yolanda Harrell

Audio Quality-Good

Location-Seneca, SC

Side 1

1:20--Harbin's maternal grandfather was a cotton farmer. He didn't know his maternal grandmother because she had died while he was young. They were originally from Ergo, SC before moving to the Clinkscales division in Seneca, SC. His paternal grandparents were also farmers.

3:30--Uncles and aunts that are recalled on his father's side are John, who lived in Atlanta, and Lula, who also made her home in Atlanta.

4:34--Harbin's family owned their own home. It was on Sheila Ferry Road in the Oakway Community.

7:40--His family is buried at St. Paul's Baptist Church at Earl's Grove, SC. Most graves are marked.

8:10--Nothing has really changed in regards to the ways in which funerals have been conducted over the years. The biggest changes Harbin can see is that in the old days, people rode around in buggies and wagons.

9:25--Mr. Harbin left for Florida to find work in 1926. His father had left the previous year for Florida in order to find work clearing land. He had two uncles who he believes worked on the railroad.

10:55--Some jobs that were open to black men other than farming work could be found at Orr Mills. Women did mostly domestic work.

12:25--The family did their shopping in Westminster and Seneca. Most often whites owned the stores, though Harbin can remember a black individual named Bennie Ware who ran his own store.

13:10--Clothes were both bought and handmade. The nicest clothes were only worn to church. Men wore over-alls.

14:11--The family raised their own fruits, vegetables, and livestock. Working the crops was tough, especially for child, because they just wanted to play and have fun. The only food products that had to be bought from the store were coffee and sugar.

15:51--Most furniture in his parent's house had been bought at local stores.

16:49--Special talents that the family was known for included blacksmith work.

17:30--Though his family never really discussed it, Mr. Harbin got the impression that times were hard in the old days.

18:30--A relative on his father's side and an uncle on his mother's side served in World War I. Harbin doesn't believe they left the country.

19:10--The family belonged to the Baptist denomination. They attended St. Paul's Church in Fairplay, SC. Harbin can recall Reverend Galloway, who preached there Harbin was young. Mr. Galloway farmed in addition to preaching.

21:39--Camp meetings were held locally in the fall at Bethel Grove. Services lasted around a week and were multi-denominational in nature.

23:30--Singing conventions were held annually at different churches in the Seneca area. An uncle of Harbin's named Tom Gideon was president of the local convention. Most of Mr. Harbin's family usually attended the conventions.

26:08--Education--Harbin attended a one-room school in the South Union community. He had to walk 2 1/2 miles to and from school everyday. The school semester lasted from September through March, with an additional short period in July and August. The typical school day lasted from 9am-4pm. Several of the teachers that he can recall are Cora Benson, Betty, Ollie, and Essie Glenn, and Cadelia and Finley Scott. Several of these were siblings. All received training at the Seneca Institute; they were essentially teaching as student teachers at Harbin's school. Harbin's parents were educated, but he doesn't know where.

31:43---Audio ends.

Side 2

00:50--Harbin got eight years of schooling; he farmed thereafter. His sister Eunetta attended Seneca Junior College. She did domestic work in Greenville, SC.

3:30--Newspapers and books were provided to the household by Harbin's parents, but he cannot recall any specifics.

4:42--Harbin cannot recall being taught black history.

10:02--The only lynching he can remember is the incident involving Mr. Green of Walhalla.

11:23--Within his family, men were considered the head of the household.

12:17--He occasionally heard his parents talk about black/white relationships and mixed children.

13:30--His maternal grandmother was part Native American.

14:00--The family rarely went to Greenville or Anderson in the old days. There were likely more opportunities there in his estimation largely due to population.

15:28--Celebrations--during July 4th celebrations, families would gather to have picnics, and the men would play baseball games. Santa Claus brought gifts and fruits at Christmastime. In the old days, most people didn't celebrate birthdays or anniversaries.

19:45--Adults in those days were strict disciplinarians; they were firm with their children.

21:56--Mr. Harbin has always accepted being black; he has been well pleased with his life.

24:02--Audio ends.

Douglas E. Harbin was born in 1909, the son of Seaborn and Lillie Scott Harbin. He was married to the former Leola Harris. He died in April 1998.

-

Speakers-Agnes Greenlee, Matthew Oglesby

Audio-Good

Location-Clemson, SC

Cassette 1

Side1

1:28--Greenlee recalls her family background, including her maternal grandparents Barry and Mary Simpson. Greenlee's parents lived between Central and Calhoun, SC. Her grandparents were slave, but any specific stories have faded from her memory. She recalls aspects of weddings and funerals in the black community as well as her relatives (Greenlee's) through marriage

10:30--She describes old family pictures, identifying individuals and their occupations.

13:00--Aspects of farming and the cultivation of tobacco are recalled.

15:55--The family went to Pendleton, SC during some weekends in order to earn additional money working crops. Her father occasionally went to Alabama in order to work in the coalmines.

19:50--Greenlee recalls her family's shopping habits, tending to fruits, vegetables, and livestock, and homemade clothes.

24:11--Furniture was both bought and handmade depending on the piece.

25:52--Quilting and making baskets were talents that her family was known for.

29:00--She can recall the flu epidemic of 1917-1918. There was sickness, but no family members died.

30:52--Greenlee makes brief mention of her uncle Dillard Walker who served in World War I.

31:35--Audio ends.

Cassette 1

Side 2

00:20--Greenlee recalls church life in the black community with her home church Abel, as well as the activities of other local black churches. She discusses camp meeting, singing conventions, and church affiliated interest groups. Whites and blacks occupationally came together during funeral services.

9:37--She recalls aspects of her education, the school building, her teachers, as well as the educational levels of her grandparents. Her brother was the first in the family to attend college. Differences in black and white schools, as well as curriculum are discussed.

24:00--Social issues in the black community are covered. Blacks were often blamed by law enforcement for crime in the area. Marriage relationships were equal in her parent's household.

31:47--Audio ends.

Cassette 2

**Note** this interview took place February 21, 1990, the day after the first interview. This is not a follow-up interview, however. The same questions are asked, and Mrs. Greenlee gives similar answers.

Side 1--30:00 of audio.

Side 2--18:00 of audio.

Cassette 3

Side 1

1:25--She occasionally went to Anderson, SC as a youth in order to visit with family who lived there. She never went to Greenville, SC as a youth.

3:05--During Thanksgiving celebrations, the men would hold "shooting matches" where they shot at targets for prizes. During Christmas friends and family would put up trees and exchange gifts. Another Christmas tradition was to have "fireball parties" out in the fields. Birthday parties were celebrated with cake and presents.

5:30--Her mother's most prized possessions were her quilts and embroidered pieces. Women would hold quilting parties and treated the occasion as a social event. Her father prized music and singing, as well as hunting.

8:03--Mrs. Green most admired her grandmother for her tireless help around the house.

10:38--Her fondest childhood memories are of singing with her family.

11:05--Mrs. Green didn't feel different because she was black. She got along with whites quite well. She wouldn't really change anything about her life.

13:25--Audio ends.

Cassette 3

Side 2

Blank

Mary Agnes Greenlee was born April 23, 1905 in the Ravenel area in Seneca, SC. She was the daughter of Lindsey and Maggie Simpson Walker. Mrs. Greenlee died on January 14, 1998.

-

Speakers-David and Nancy Green, Vennie Deas-Moore

Audio Quality-Good

Location-Clemson, SC

Side 1

2:15--Mr. Green was born in the area known as "The Quarters" near Clemson, SC. He is unaware of where or when his parents were born.

5:10--His parents worked as sharecroppers; his mother was a very hard working woman who taught the children life lessons.

6:25--Mr. Green recalls as a youth washing clothes at "The Branch." He describes the common steps utilized in the washing process such as using a "battling" stick to remove dirt from the clothes.

8:45--He names his siblings: (he speaks in a low tone here, so it is hard to understand) Annie Mae, Rebecca, Pauline, Celina, Robert Lee, Chris, and John Henry. An additional name is not audible enough to understand.

10:30--Mr. Green's mother died of the flu during the epidemic of 1917-1918. Everyone in his family got sick except for he and his father. There was much sickness in the community during that time period.

12:07--Mr. Green's father Edward worked as sharecropper and sold his own produce. Mr. Green can remember his paternal grandparent's names: Sammy and Tiesha.

13:43--Slavery--issues regarding slavery were never really discussed in the Green household.

14:15--Funerals/burials--most of Mr. Green's family is buried at Abel. There were no written headstones in those days; an unadorned stone usually marked the spot. He can recall funeral processions in which the caskets were pulled by horse or mule. There was no embalming in those days. "Wake's" were held at the home of the deceased. Prior to being placed in a casket, the deceased were usually placed on a "cooling board" and covered in a white sheet. He recalls the work of the Burial Aids Society. They would mourn at funerals and place flowers at the grave as well as provide monetary aid to grieving families.

21:34--Marriages/weddings--Mr. Green cannot provide any detail on how weddings were conducted. He and his wife didn't have a wedding; they just got married at the local preacher's home.

22:56--Mr. and Mrs. Green had five children: David, Jr., Matthew, Elizabeth, Anna, and Katie.

23:30--Mr. Green had a brother who moved north and made his home in Cleveland, OH.

24:56--He has a pocket watch that has been passed down from his great-uncle.

25:12--Mr. Green had been a freemason since the 1940's. His wife is a member of the Eastern Star.

27:23--The interviewer is interested in what types of jobs were available to blacks. Other than sharecropping, Clemson College provided employment. Mr. Green worked at the Clemson College dining hall. Women did laundry at the college or did domestic work for families. Younger people farmed in order to earn money.

29:44--Mr. Green and his family usually did its shopping at the local stores in Clemson. They used the credit system to pay for goods. The family raised much of its own food.

31:02--Furniture was bought from stores in nearby Central, SC.

31:33--Audio ends.

Side 2

00:45--As a youth, Mr. Green can recall black women in the community getting together during certain times of the year to do quilting projects.

1:33--Mr. and Mrs. Green cannot recall having ever used cribs for babies. Children did have toys; they were usually received once a year at Christmas.

4:29--Church--Mr. and Mrs. Green are Baptists and attend the local Abel Baptist Church. They can recall that camp meetings were held more frequently in the past. Meetings were held in September. The Green's describe a festival-like atmosphere surrounding the event; many individuals treated the occasion as a family reunion. The preacher would preach from inside the church; the congregation would remain in the church with him. The doors of the church would remain open, however, and huge crowds would gather outside in order to hear the services.

10:20--Education--Mr. Green never got to attend much school, because his services were often needed in farming work. He attended when he could, mostly in the winter. His parents didn't attend school.

11:34--Cotton--workers were not required to pick a certain quota per day. Workers would often aim for 100 pounds per day, though the task was extremely difficult to accomplish. Workers were not paid every day; rather they were given a lump sum.

13:09--All of Mr. Green's children attended college.

13:20--Mr. Green names a few of his children and their occupations.

15:37--White/black relations--Mr. Green states that he didn't really have much interaction with whites. His wife states that things were "hard" for her in those days, but will not elaborate further. Law enforcement didn't seem to be a problem in Mr. Green's estimation.

19:20--Celebrations--the black community celebrated "Watch Nights," camp meetings, and baptisms. The freemason's held "Turnouts" in June around St. John's Day. Emancipation Celebrations were held during the first of the year.

23:17--Mr. Green never thought of himself as being different as in terms of being black; he played with whites as a youth.

24:34--Deas-Moore concludes the interview.

24:16--Audio ends.

David Green, Sr. was born on August 7, 1907 in the area around Clemson, SC known as "The Quarters." He was the son of Edward and Tiesha Green. Mr. Green began working at the Clemson College dining hall when he was around the age of 25. He and his wife Nancy had 5 children: David, Jr., Matthew, Elizabeth, Anna, and Katie. Mr. Green died on October 9, 2003.

-

Speakers-Alice Gassaway, Yolanda Harrell

Audio-Good

Location-Seneca, SC

Cassette 1

Side 1

00:47--Miss Gassaway's parents were Larkin Dial and Anna Gassaway. She did not know either set of grandparents.

1:22--Several family members moved away from the Seneca area for economic reasons. She had an aunt named Livonia and two brothers who moved to Detroit, Michigan, three sisters who went to Cleveland, Ohio, and another brother who made his home in Charlotte, North Carolina. Miss Gassaway's father went to Cleveland by himself for three years, but returned to Seneca and the rest of the family.

6:44--Her father was a carpenter and farmer, while her mother did domestic work for local families. They owned their own home.

8:26--Miss Gassaway discusses aspects of farming and crops that were commonly grown when she was a youth as well as care for livestock. The family really didn't need to buy anything but sugar and coffee; everything else was produced on the farm.

11:45--Slavery--Miss Gassaway did not know either set of grandparents, so any recollections of that time-period came from her mother. Miss Gassaway's maternal grandmother was black, but her maternal grandfather was a white man. She only assumes that he was a slave master. She later recalls that his last name was Acker. Her maternal grandmother also had children by a black man. The mixed-race children lived in the master's house, while the black children lived along with the grandmother in the "cabins" (slave quarters?). Her grandmother struggled to make ends meet for her black children, while the mixed race children were treated with privilege. Miss Gassaway's paternal grandmother was a white from Holland, her paternal grandfather was black.

16:40--Miss Gassaway relates a story of when one of her uncles had to leave the Anderson, SC area on account of threats from the local Ku Klux Klan in the 1920s. He relocated to Cleveland, Ohio.

21:03--Her father did carpentry work; he along with the Sloan's helped build St. James Church.

23:26--The entire local family is buried in Oak Grove Cemetery; the graves are marked.

24:33--She recalls a local named Carrie Arthur and details of her wedding during the 1920s. Several other family members and relations are mentioned.

30:04--Miss Gassaway briefly describes old family photographs.

31:42--Audio ends.

Cassette 1

Side 2

00:07--Gassaway explains that some of the children's nice shoes and clothes were donated by whites that her mother worked for. She mentions Dr. Austin's (he was the local dentist) wife and Mrs. Hunter (her husband ran the local shoe store).

2:10--Miss Gassaway recalls helping her mother do the wash as a youth. She would carry the clothesbaskets on head, hips, or shoulders. She describes the steps commonly utilized in the washing process. Homemade lye soap was often used. Pay was not good; they made perhaps $1.50 per load.

9:25--In order that Miss Gassaway could attend school, her mother sold a cow for $75 and also mailed monthly payments to her daughter at school with earnings from her domestic work.

11:36--Her mother worked Monday through Thursday washing and ironing for local whites. In the days before electric irons, her mother would have eight or nine irons available, all heated in the fireplace. The general steps in the ironing process are covered. There was no extra charge for ironing.

14:00--Different charges according to the size of the wash are discussed.

16:17--Miss Gassaway briefly left the Seneca area for New York. About three years after she first started teaching, she decided to move. Domestic work up north at the time was proving to be lucrative for blacks, so she decided to give it a try. She recalls several stories of her experiences before her return to the Seneca area.

26:16--Miss Gassaway recalls the types of jobs that were commonly available to blacks. Black men usually farmed or did odd jobs. Many did blacksmith work. There were really no employment opportunities for black women other than domestic work. Young blacks often did baby-sitting work.

29:40--Shopping--The family shopped at Hunter's Store in Seneca. They used the credit system to pay for the goods. Miss Gassaway was aware of no black-owned local stores.

31:44--Audio ends.

Cassette 2

Side 1

00:20--Clothes were occasionally purchased from families her mother worked for. Girls usually wore "house dresses" while boys commonly wore over-alls. The nicest outfits were only worn on Sundays.

6:30--Miss Gassaway explains that her oldest sister attended a nursing school in Raleigh, NC. Another sibling went to Seneca Junior and then attended Claflin in Orangeburg, SC. Another went to Benedict in Columbia, SC.

12:00--Furniture--Her father made the dinner table himself. It had benches that would seat five people on each side. Her father would sit at the head of the table. The iron beds in the house were store-bought.

14:55--Her father was expert at making baskets, while her mother made quilts, curtains, pillowslips, and underpants. She also did crochet work. Indeed the family talents seemed to lie in making clothes, hats, etc.

18:55--Miss Gassaway doesn't remember her childhood being particularly difficult; her parents were good workers and always strove to provide for the family.

20:23--She understands that her maternal grandmother had a particularly hard time during the days of slavery. The story regarding her white grandfather and black grandmother are again recalled.

25:07--Miss Gassaway can recall the flu epidemic that occurred around 1917-1918. There was lots of sickness, but she cannot recall anyone in her family dying from it. Dr. Bryant was a local black doctor in Seneca who treated the community.

27:00--Her brother Larkin, Jr. served in World War I. He wasn't sent overseas, however.

27:51--Church--Miss Gassaway is a member of St. James Methodist Church. Her father, along with Archie and Elijah Sloan helped build the church building. A few of the preachers that can be recalled are Reverend Thompson, Reverend E.C. Wright, Reverend Getty, and Reverend Robinson. St. James traditionally buried its members at Oak Grove Cemetery. Camp meetings were often held at Bethel Grove.

31:45--Audio ends.

Cassette 2

Side 2

00:07--Miss Gassaway never attended camp meetings until she was nearly an adult. The meetings were held in mid September and usually lasted from Monday until the following Sunday, where enormous crowds were sure to gather. Services were multi-denominational, and usually lasted from 7pm-11pm.

3:45--Among her favorite songs are: How Great Thou Art.

4:14--The interviewer is interested to know if blacks and whites ever worshipped together. Her first experience with such an occurrence was when she was picked as a delegate to represent her church at a Methodist conference in Columbia, SC. Although both groups were housed in separate buildings, they ate and worshipped together.

6:21--A particularly influential civic group was the "Willing Worker's" female youth group at her church.

8:02--School--She first started school at age six at an all black school located on Pine Street that covered all grades through seven. It was called Seneca Graded Public School. She names her teachers: Katie Hicks (first), Ida Sloan (second), Miss Willie Grant (third), Lillie Shaw (fourth), Carrie Benson (fifth), Julia Collins (sixth), and Principal J.T. Burris (seventh). There were perhaps forty people per class. The school year lasted seven months. The school day lasted from 8am-2pm.

16:23--After graded school, Miss Gassaway attended Seneca Institute followed by two-year stays at Claflin and SC State. Following SC State, she taught for three years in Liberty, SC. She spent a short time in New York before returning to the Seneca area where she taught fourteen years at Abel. After desegregation, she taught at Pickens Elementary School.

27:36--The achievements of famous black people such as Frederick Douglas and Booker T. Washington were taught in black schools. The children also read books by Langston Hughes.

29:30--She describes the dimensions and general layout of the Seneca Graded Public School building.

31:43--Audio ends.

Cassette 3

Side 1

00:30--A few of her favorite games at recess included "give that girl a piece of cake," "blue bird in my window," and "drop the handkerchief." She explains the rules of a few of these games. Jump rope and hopscotch were also popular. The boys usually played baseball.

6:20--Miss Gassaway fondly recalls her high school drama class, and productions such as Everywoman.

10:17--Social clubs/organizations--she had a couple of sisters who were members of the Eastern Star. Meetings were held in the local "Odd Fellows" hall.

11:30--Politics--though some blacks were afraid to vote when first given the opportunity, her father never hesitated to be involved and never missed an occasion on which to exercise his right to vote.

13:43--Lynching--she knows of the incident involving Allen Green of Walhalla, SC. It seems that Mr. Green was a horse trader, and during one particular transaction with a group of whites became involved in controversy that led to his death. After successfully selling a horse, the whites left for a short time in order to buy other supplies in town. They were to be gone just a short time, so one of the white ladies stayed behind with Mr. Green. Upon returning to Mr. Green's business, they were informed by the white woman that Mr. Green had raped her. Authorities arrested Mr. Green, but a mob appeared at the jailhouse, broke Mr. Green out, and subsequently lynched him. Mr. Green was beaten and shot over 100 times.

18:06--Local law enforcement was not a real problem in her estimation.

18:30--Marriage relationships were equal within her family.

19:14--Miss Gassaway discusses mixed race relationships, mulattos, and individuals who tried to pass for white.

22:00--Celebrations/holidays--Halloween, Christmas, and Thanksgiving were the most important events. Christmas was her favorite; though she was concerned that Santa Claus seemed to like white children better, because they always got nicer gifts. Birthdays were never really celebrated.

25:55--The family house was heated by a large fireplace.

29:39--Her mother's most prized possessions were her quilts; they were all burned in a house fire. Her father prized his hunting dogs.

31:19--Audio ends.

Cassette 3

Side 2

00:37--Her father had four hound dogs. They were not pets; she was not allowed to play with them.

1:08--Two individuals that she liked and admired were Carrie Arthur and the wife of one of the local preachers named Katie. The two were always involved in church activities and strove to always help the needy. Miss Gassaway always tried to live up to the example they had set.

5:35--Miss Gassaway thought nothing of being black. She has always enjoyed living in Seneca and her relationships with whites and blacks has been rewarding. She admits that this outlook is in sharp contrast to her father, who disliked whites immensely. This attitude likely was born out of the incident in which his brother was forced to leave Anderson, SC by the Ku Klux Klan. Her mother was much more understanding and got along with whites quite well.

9:15--Miss Gassaway names her fifteen siblings: Lula, Minnie, Lena, Hattie, Mamie, Carrie, Annie, Alice, Waymon, Milton, Larkin, Jr., Clarence, Charlie, Sylvester, and Lafayette (?).

13:05--If she had the opportunity to live her life over again, Miss Gassaway would not change a thing. She had good relations with whites, a good childhood, and good friends.

14:40--Altogether, Miss Gassaway was an educator for thirty-eight years. She retired in 1970.

16:03--Harrell thanks Miss Gassaway for the interview.

16:12--Audio ends.

Alice Gassaway was born in the Seneca, SC area circa 1904-1910. She was the daughter of Larkin Dial and Anna Gassaway of Seneca, SC. After attending South Carolina State College, she taught in the South Carolina public school system for thirty-eight years. She never married. Ms. Gassaway died on October 4, 1994.

-

Speakers-Thomas Dupree, W.J. Megginson, unknown female speaker

Audio Quality-Good

Location-Clemson, SC

**Note** cassette one, side one was apparently not recorded--the first available audio indicates that the interview has been underway for some time prior. Also, side two as stated by Megginson is actually side one on the user cassette. In addition, these interviews were originally part of a research project regarding the town of Calhoun, SC. They were later moved to complement the Black Heritage in the Upper Piedmont Project.

Cassette 1

Side 1

00:42--Dupree discusses local street names in the black community. Local streets that are named Shaw, Brewster, Stevens, Pressley, etc. are all named after local black families. Mr. Dupree thinks these streets were named around the time of the late 1970s or early 1980s.

4:00--Recollections of his mother and the steps that were involved in washing at local wells and springs. Washing utensils were left at the spring in order that they could be used at all times by whoever needed them.

6:14--The local lady known as "Aunt Amelia" was related to Mr. Dupree. She worked for people in and around Calhoun, SC while his mother worked for people in Clemson, SC. Neither group made any more than the other in terms of wages.

10:15--Church--Mr. Dupree has attended Abel Baptist his entire life. He thinks that "Little Abel" church eventually became New Hope across from the Old Stone Church. Abel held church services once a month. A few preachers that can be recalled are: John Watson, Broaddus, Beech, and Collins. Abel met on every second Sunday, while Goldenview met on the first. The longtime bookkeeper at Abel, Suzy Haywood is recalled.

18:14--Megginson briefly mentions Suzy Haywood's father Harrison who, along with other local blacks, were involved in the lynching of a white man who had raped one of Mr. Harrison's daughters. The governor pardoned these men.

20:23--All of Mr. Dupree's relatives are buried at Abel Cemetery. He discusses aspects of burials and funerals in the black community.

24:30--Megginson is interested in who was responsible for digging local wells. The Hawthorne's and Green's are mentioned by name, Mr. Dupree dug several himself.

25:57--Mr. Dupree never attended school. Alec Dupree was a relative involved in local school life. He briefly taught at the local black school after graduating from Benedict College. He and his wife Elvira had a house and land in the Keowee area.

29:34--Mr. Dupree explains the differences in "country work" vs. city or "inside work."

31:14--Audio ends.

Cassette 1

Side 2

Blank

Cassette 2

Side 1

00:25--Mr. Dupree recalls the long workdays that local blacks had to endure. He describes a typical workday using his aunts as an example.

2:50--His brother-in-law John Whitt worked for Clemson College. College employees were paid by the month. He names other individuals who worked around the College.

6:53--The John C. Calhoun slave quarters had already been torn down when he was a youth.

7:20--Aspects of the Greenlee and Brewster families are recalled such as where they lived and what types of work they did.

12:20--The first black family to own a car in the community were the Reid's.

13:23--In their free time as youngsters, blacks would occasionally play with local whites.

15:35--The Dupree family utilized their own livestock and vegetable gardens, but also bought goods from the local Boggs and Smith stores. He discusses purchasing issues and the cash or credit system.

18:24--Aspects of the local cotton trade are discussed.

24:47--Megginson is interested in what types of work Mr. Dupree was involved in. He explains that permanent employment was not widespread in those days. Most people did farm work and odd jobs. The Clinkscale and Galloway families had large farm operations.

26:57--There was a local lumberyard opposite where the local Holiday Inn is located. He states that it was known as the old "Boon Place." Work there was dangerous, involving large saw-blades and floating logs down the river.

30:50--Audio ends.

Cassette 2

Side 2

00:57--Mr. Dupree discusses how the Aaron Boggs land was divided after his death. His daughter Myra Boggs Payne had rental houses located where the local Ramada Inn is now. This area was called the "Payne Quarters." She charged between 2 1/2 and 5 dollars rent each month.

3:47--The best local wages Mr. Dupree ever received were from the railroad. The construction of the double-track directly affected wages in the Calhoun/Clemson area. The railroad simply paid out better wages than the community, so in order to keep employees from going to the railroad, most local wages were increased. Mr. Dupree discusses the life of a railroad worker.

10:12--Mr. Dupree recalls the Smith boarding house and the George Shaw farm.

14:52--Megginson is interested to know of the most prosperous families in the black community. Butler Reid seemed to do quite well. He worked a large portion of farmland that he rented from the Boggs family. He even owned his own grocery store located in front of Goldenview Church.

16:30--The changes in the direction of the railroad and its impact on the local community is discussed.

20:00--More often than not, clothes were made at home utilizing cloth bought at local stores. Mr. Dupree's mother used a Singer sewing machine to make clothes and quilts.

22:04--Mr. Dupree was married to the former Elizabeth Butler. Her parents were Ike and Ellie Butler. The couple was married at a pastor's house in Seneca. They had eight surviving children. Mr. Dupree's wife did some domestic work, but most often focused on the home and helping to raise the children.

28:08--All of Mr. Dupree's children attended school.

29:30--The Depression didn't really affect him. Times were hard for his community prior to the national troubles, so getting by on very little didn't have a huge impact.

31:43--Audio ends.

Cassette 3

Side 1

00:14--The experiences of blacks that served in World War I is touched upon.

1:55--Mr. Dupree can remember the flu epidemic that occurred around 1917-1918. His recollection is that fatality rates were low where he lived out in the country compared to the more populated areas.

3:15--Three of Mr. Dupree's son served in World War II. Although he doesn't elaborate, he gives the impression that this experience made more of an impact for blacks than what had occurred with the previous World War I generation.

4:43--Megginson mentions the local Singleton family and specifically Mrs. Singleton the educator in Calhoun. This sparks a conversation between Megginson and the female speaker. Mr. Dupree never attended school.

10:14--Megginson encourages Mr. Dupree to talk about everyday life in the black community, including holidays. Mr. Dupree talks of days when families were close-knit; living and eating meals together. At Christmas, people would shoot fireworks and leave out stockings for Santa Claus. Gospel singing groups occasionally came to town. Camp meetings at Bethel Grove were common.

16:35--Megginson thanks Mr. Dupree for the interview.

17:28--Audio ends.

Cassette 3

Side 2

Blank

-

Speakers-Cassette I (Mr. and Mrs. Allen Code, Vennie Deas-Moore) Cassettes II-IV (Allen Code, Yolanda Harrell)

Audio Quality-Good

Location-Seneca, SC

Cassette 1 (April 20, 1989)

**Note** this cassette was not originally a part of the Black Heritage in the Upper Piedmont Project. This field research conducted by Deas-Moore was added to complement the Black Heritage in the Upper Piedmont Project.

Side 1

5:40--Church and school were two of the most important and active aspects of the black community. Mr. Code attended St. James United Methodist.

6:37--Emancipation Celebrations--these were celebrated in the days before the Civil Right Movement. They were usually school-sponsored; patriotic and Negro spirituals were performed, and there was usually a guest speaker.

8:40--Watch Night services were held in the black community on New Year's Eve at local churches.

9:06--Local black churches were crucial in the organization of events for children and the community as a whole.

10:20--The white and black communities would each sponsor their own Negro History Week. Mr. Code was often asked to be the guest speaker at local white churches.

12:30--Local blacks would often have picnics and BBQ parties in Highpoint, NC.

14:00--Mr. Code reflects on the cattle-culture of the old days, and aspects of the local farmer's markets that were held in late fall.

19:23--Camp Meetings--this was a multi-denominational event in the black community. They were usually held in the summer, and lasted perhaps a week. These were festive events, as it was treated as a sort of homecoming for family and friends.

31:14--Audio ends.

Cassette 1

Side 2

Blank

Cassette 2 (June 1990)

Side 1

00:30--Mr. Code provides some biographical information. He is one of ten children in his family. Birthdays were not celebrated on account that they could not be all recalled. He knew of "about" the time of year he was born, so he was free to choose his own birth date.

1:50--Paro Code (Doc) was his father. Esther Code was his mother. He discusses his grandparents and his Uncle Richard.

6:59--His parents owned their own home. It was a four-room log cabin with a separate kitchen in the back of the residence. Mr. Code's grandparents built the house.

10:20--Slavery--Mr. Code's grandparents were slaves. He recalls the story of finding the family of a long lost uncle that had been sold and moved to Florida during slavery.

14:40--The older members of Mr. Code's family are buried in Salters, SC. The graves are not marked with headstones.

15:20--The only old tradition he can remember in regards to marriage is his grandmother "stepping over a broom." He is unaware of the significance of this tradition.

15:57--Mr. Code has been married twice. His first wife was Sedelia Blassingame of Seneca. She died of MS in the early 1980's. He was later married to the former Susan Green of Pinewood, SC.

18:03--Mr. Code's parents were farmers in the low country of South Carolina. The set of grandparents that he knew were slaves and worked the land, though they bought there way out of slavery before 1863. This is how Mr. Code's father was able to inherit the family cabin and adjacent land.

23:51--Typical jobs available to black men in the old days were working on railroad steel gangs, section hands, farming, etc. Women did domestic work. Young people were allowed to farm on the weekends provided they sign a contract with the owner of the land.

30:42--The subject of shopping is briefly brought up.

31:30--Audio ends.

Cassette 2

Side 2

00:23--The two continue to discuss aspects of shopping. When he was a youth, the family would make one big shopping trip a year in order to purchase school clothes and shoes. Whites owned all of the store establishments.

1:55--Food items such as vegetables, livestock, and wheat were raised at home. Sugar was made from sugarcane, and tea was utilized from sassafras.

5:40--Most of the furniture was store-bought.

8:30--Mr. Code still owns a quilt that his mother made from suit samples. While purchasing suits in the old days, small cloth samples were given out to customers in order that they could inspect the fabric and its texture.

9:29--Mr. Code had a musically talented brother who could sing and play the guitar. His mother was quite in demand for her seamstress work.

12:25--When Mr. Code was a youth, he could recall the older members of his family speaking of hard times. His mother experienced an earthquake when she was young. Mr. Code himself can remember the flu epidemic that struck between 1917 and 1918. He was around ten years old during the outbreak. He was the only one in his family not to become ill. Everyday responsibilities were left to him; there was only one doctor (white) locally and a great deal of time passed before he could see everyone. The experience taught him how to be independent.

21:00--His two older brothers served in the Army during World War I, but did not go overseas.

22:12--Church--as a youth, he was a member of the African Methodist Episcopal denomination. After he moved to Seneca, he joined St. James United Methodist. Baptist churches were also very influential in the black community. Mr. Code has attended only one camp meeting since moving to Seneca. His experience was negative, and he has never attended one since. Many in the enormous crowd seemed not to respect the spiritual nature of the event, opting instead to facilitate a party-like atmosphere with rowdiness and alcohol. Law enforcement was brought in, and scores were arrested.

31:46--Audio ends.

Cassette 3 (June 1990)

Side 1

00:30--Tape II of Yolanda Harrell's interview--tape III overall--camp meetings were multi-denominational events.

2:05--Mr. Code occasionally attended singing conventions. These were held more frequently in the summer and usually lasted only one day. One of his favorite church songs was Trust and Obey.

4:30--Did blacks and whites ever worship together? He believes that the Pentecostals may have had mixed services occasionally.

5:57--School/Education--he was around six years old when he started his education at Pinewood Elementary. There was a large hall upstairs with three schoolrooms downstairs. There were three teachers for the three classrooms. The children wrote on slates and sat on pew-benches. The school day lasted from 9am-3pm. Lunch was brought from home. From the seventh grade onward, he attended Kendall Institute in Sumter, SC. Mr. Code names some of his siblings and their education. Mr. Code himself attended Temple University for one year, where he was third in his class. He graduated from Benedict College in 1935 with a degree in Biology. He then went on to receive a Masters in Education from the University of Michigan in 1955.

31:37--Audio ends.

Cassette 3

Side 2

00:19--Educational issues continue to be discussed including his time on the Wofford Board of Trustees.

2:00--Newspapers/reading materials in his household as a youth included The Pittsburgh Courier and The State.

3:25--Differences between white and black schools are discussed.

12:20--The "Code" surname--the Code surname was originally spelled "Cord." Because of regional dialects, the family despite the spelling always pronounced the name "Code." Mr. Code took it upon himself to have the spelling of the name changed in order to avoid confusion. He is unaware of how the family surname originated or its significance.

18:30--He learned "the hard way" about how whites sometimes treated blacks. He admits to being a proud and independent young man whose confident attitude sometimes led to trouble with whites. Mr. Code relates a lengthy story of his youth as a worker in Florida, and the troubles he experienced with his white overseer.

31:46--Audio ends.

Cassette 4 (June 1990)

Side 1

00:25--Lynching--Mr. Code is aware of two incidents. One that he only heard about was of the killing of a man named Green that occurred in the Walhalla area. The other incident occurred to an individual he knew when he was a youth in Pinewood. There was a local "hermit" named Joel who lived in the wilderness of the Pinewood area. He would occasionally visit Mr. Code's family and other black locals in order to have items from the grocery store picked up for him. He had always been immensely afraid of whites and was fearful about going into town or being around any kind of modernity. On one occasion it was found that the local store had been burglarized. The authorities were instructed to "...look for a black man" with the aid of bloodhounds. The bloodhounds had initially led the authorities to a white man's house. They then took the hounds into the black community. The hermit Joel had been picking up supplies from a local black family, and began to flee when he saw the white law enforcement with their dogs. They immediately joined the chase, and what proceeded was a tragic standoff in which the hermit killed a bloodhound and two law enforcement officers. Joel was eventually shot, dragged through the streets, and lynched.

5:00--When Mr. Code was young, it seemed that the duty of law enforcement was to pin crime on blacks and have them arrested.

6:14--Marriage/relationships--the men of Mr. Code's family were considered the "boss." He states, "...whatever he said was law and order."

6:50--Black/white romantic relationships were frowned upon. The black community treated mulattos differently. Mr. Code states that "...mulattos worked in the home, darker hues worked the crops."

14:40--Celebrations/holidays--the black community celebrated July 4th holidays with dancing, picnics, and sports. Aspects of the Thanksgiving and Christmas holiday celebrations are recalled.

18:10--"Hot Suppers"--these were large, prepared meals in the black community for which a fee would be charged. These were utilized either for charity or the raising of personal funds.

21:20--Mr. Code's father prized his hunting dogs. His father was considered an expert dog-trainer, and many whites sought his assistance.

23:45--The individual that Mr. Code most admired as a youth was Reverend O.A Parker. Reverend Parker was the principal at Mr. Code's middle school, and became a mentor of sorts to him.

31:35--Audio ends.

Cassette 4

Side 2

00:30--Mr. Code briefly recalls family life; his first wife died of Multiple Sclerosis. He married his second wife Susan Green in 1984.

2:41--Harrell asks Mr. Code what his favorite activities as a youth were. This gives Mr. Code an opportunity to reflect on his baseball career. Mr. Code was a talented baseball player, and played in several semi-pro leagues in Florida and Pennsylvania. As a pitcher, he lost only one game over a nine-year period. Good money could be made in the summer semi-pro leagues. He talks about the art of pitching and the different pitches that were in his repertoire such as the "curve-ball," "fade-away," and "turkey-drop."

13:40--Code Elementary in Seneca is named for him. He discusses the honor and his long career in education.

20:30--Mr. Code discusses the struggles and problems that black principals in his era often faced. As a black man in a prominent leadership position, he was initially distrusted by the black community. That aside, problems with whites were common, and Mr. Code relates several stories of his experiences. One area of strong support however was the local school board.

26:51--Harrell thanks Mr. Code for the interview.

27:32--Audio ends.

-

Speakers-Ida Mae Clinkscales, Vennie Deas-Moore

Audio Quality: Poor. Mrs. Clinkscales is seated too far from the recorder for her answers to be clearly discernible.

Location-Seneca, SC

Side 1--28:34 of audio.

Side 2--Blank

-

An interview between Yolanda Harrell and Velma Childers. Velma Childers was born on November 6, 1902 in Seneca, SC. She was the daughter of Thomas and Fanny Scott Gideon. She taught school in the local area for 36 years. She died on December 20, 1997.

-

Speakers-Anna Reid, Jack Brown, Lucinda Reid Brown, Lucy Reid Brown McDowell, Vennie Deas-Moore

Audio Quality-Good

Location-Clemson, SC

Side 1

**Note** this interview was not originally part of the Black Heritage in the Upper Piedmont Project. This field research conducted by Deas-Moore was added to complement the Black Heritage in the Upper Piedmont Project.

00:07-8:10--Anna Reid gives a brief biographical statement before Mrs. Reid Brown begins to speak. Mrs. Reid Brown discusses her age and gives a short family history. She states that her grandfather was one of John C. Calhoun's slaves. She begins to recount several stories; one involves her first husband's death on the way to Fourth of July picnic. Other recollections include childhood experiences with games, birthdays, picnics, dancing, and listening to music on a victrola. The interviewer is curious about talented family members; Mrs. Reid Brown states that her daughter Lucy Reid Brown McDowell was a very talented tap dancer.

8:13-11:38--Lucy Reid Brown McDowell is now speaking. She gives brief biographical information before detailing when and where she learned to dance. She can remember dancing with a live band, and also being able to do the "Jitterbug."

11:41-20:05--The focus of the interview returns to Mrs. Reid Brown. She first describes family celebrations during the Christmas season before recalling certain aspects of her education. When she was a child, there were no public black schools in the area, so she attendee a school set up by Abel Baptist Church. She goes on top describe special celebrations at Abel such as revival meetings, Easter Sunday, and Watch Night Service (New Year's Eve).

20:08-31:40--Deas-Moore is interested to know what children did during the summer months. Children often worked alongside their parents in the fields on sharecropping farms. She goes on to discuss family reunions that took place on her parent's birthday. Mrs. Reid Brown has traveled extensively, and gives a lengthy story about her travels to Haiti.

31:45--Audio ends.

Side 2

00:37-7:10--Mrs. Reid Brown continues to describe her travels throughout the United States before briefly touching upon her involvement with Abel Baptist Church. She then describes activities during Fourth of July and Emancipation celebrations.

7:19-17:12--Mrs. Reid Brown's son Jack begins to speak. He recalls square dances in the 1940's, and states that he was the first black person to be in the Clemson Christmas parade. He goes on to describe his employment with Clemson University, including his time running the ice cream parlor.

17:15--Audio ends.

-

An interview between Matthew Oglesby and Lucinda Reid Brown. Lucinda Reid Brown was born on March 11, 1890 in the Clemson/Calhoun area. She was the daughter of Alfred B. and Harley Reid. She married Jack Brown in 1910. They had seven children. Mrs. Reid Brown died on March 30, 1990.

-

An interview between Yolanda Harrell and Clotell Brown. Clotell Brown was born January 14, 1894 in Pendleton, South Carolina. She is a member of Kings Chapel AME Church in Pendleton. Ms. Brown lived in Pendleton most of her life. She died on October 22, 1992.

-

An interview between Kate Meacham and James Benson.James Benson was born on June 23, 1905 in Central, South Carolina. He was the son of Patrick and Annie Reese Benson. Among other things, he was the cemetery caretaker at Abel Baptist Church in Clemson, South Carolina. He died on November 13, 1992.

-

An interview between Yolanda Harrell and Cornelia Alexander. Cornelia Thompson Alexander was born August 11, 1900 in Pendleton, SC. She was the daughter of James and Lilly Grant Thompson. She died on October 3, 1996.

-

Abel Baptist is an African American church that was founded in 1868. It is located in Clemson, SC. James Benson works as the church cemetery caretaker and was also the Superintendent of the Sunday School program. The church has three cemeteries. Benson and Megginson identify grave markers, note birth/death dates, and read inscriptions [when present or legible] in these interviews. In addition, Benson provides biographical information regarding interred individuals of whom he is aware.

-

In the 1922 edition of "Taps," the senior class (the sophomores of the 1920 walkout) reflected fondly on their role in bettering Clemson.

-

In his 1923 report to the Board of Trustees, President Riggs spoke of the graduating class, who had been freshmen during the 1920 walkout. President Riggs stated that, with few exceptions, the graduating class was "more cooperative, more loyal and in general more satisfactory" than any other recent classes.

-

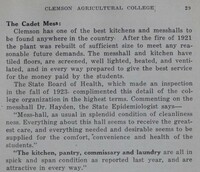

President Earle's 1924 report to the Board of Trustees included a laudatory section on the state of the mess hall, which was hailed as one of the best in the country.

-

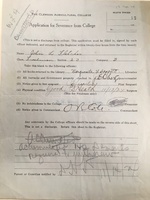

A few walkout participants, such as John L. Fletcher, requested to leave Clemson. It is unclear whether these students held irreconcilable issues with the school or if their parents did not allow them to return.

-

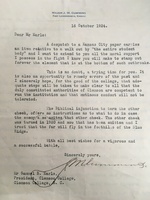

President Earle sent this letter indicating that the complaints of the 1924 walkout were unfounded.

-

The Board of Trustees issued a report on the 1924 walkout, in which they clearly showed an increase in quantity of food provided in the mess hall. They also included testimony from a state health inspector who lauded the Clemson mess hall as one of the best in the country.

-

Cadet Harold Witt sent this letter to his father following the 1924 walkout. He indicates that the walkout was not supported by the majority of Clemson students, and he had decided not to participate.

-

The walkout of 1924 was widely denounced. This fascinating letter was sent by James M. Cummins to President Samuel B. Earle. Cummins, of course, had been the Commandant at the center of the 1920 walkout.

-

The punishment of R. F. "Butch" Holohan, president of the senior class and captain of the football team, was the primary cause of the 1924 walkout.

-

In his 1921 report to the Board of Trustees, President Riggs expressed satisfaction with the new Department of Student Affairs and conditions in the mess hall.

-

Professor D. H. Henry, a widely popular teacher at Clemson, was tasked as the first Director of the Department of Student Affairs. His responsibilities included monitoring barracks, mess hall, and laundry conditions and to be a general advocate for students.

-

An article in "The Clemson Alumnus" described the new Department of Student Affairs, which was to be overseen by a widely popular professor, Dr. D. H. Henry.

-

In a two-day meeting during the summer of 1920, the Board of Trustees made substantial revisions to by-laws concerning the Disciplinary Committee, including instituting public trials.

-

In a two-day meeting during the summer of 1920, the Board of Trustees officially approved the creation of a Department of Student Affairs.

-

President Riggs offered his reflection of the 1920 walkout. He placed particular emphasis on the notion that college life had changed in the years following World War I. He insists Clemson had operated as an institution "for boys;" however, the Great War had turned many of Clemson's students into men. This disparity was the root cause of the walkout in Riggs' view.

-

President Riggs offered his reflection of the 1920 walkout. He placed particular emphasis on the notion that college life had changed in the years following World War I. He insists Clemson had operated as an institution "for boys;" however, the Great War had turned many of Clemson's students into men. This disparity was the root cause of the walkout in Riggs' view.

-

President Riggs offered his reflection of the 1920 walkout. He placed particular emphasis on the notion that college life had changed in the years following World War I. He insists Clemson had operated as an institution "for boys;" however, the Great War had turned many of Clemson's students into men. This disparity was the root cause of the walkout in Riggs' view.

-

In the days following the Board of Trustees' investigation, newspapers around the state reported on the Board's findings. The Board sided with the school administrators, but stated their intention to concede on some of the students' demands.

-

President Riggs received numerous correspondence expressing support. This letter is notable as it was sent from W. S. Currell, president of Clemson's peer institution, the University of South Carolina.

-

Several parents testified during the Board of Trustees' investigation. Here, Mr. Moss indicates that his son's desire to return to Clemson and seems to believe that his son was motivated to leave campus due to peer pressure.

-

The Commandant of the Corps, Lt. Col. Cummins, testified during the Board of Trustees' investigation. He stated his belief that the walkout was due to postwar angst.

-

A photograph of "Main Hall" at Clemson College, taken from the 1920 edition of "Taps," the school yearbook.

-

The freshman and sophomore classes drafted a formal petition with several demands including improved mess hall conditions, revisions to the Disciplinary Committee, and reinstatement without punishment of all walkout participants.

-

The freshman and sophomore classes drafted a formal petition with several demands including improved mess hall conditions, revisions to the Disciplinary Committee, and reinstatement without punishment of all walkout participants.

-

Cadet Cullum testified during the Board of Trustees' investigation. One of the most prominent features of his testimony was his imparting of student demands, including the institution of public trial for disciplined students.

-

President Riggs submitted a Special Report to the Board of Trustees following the walkout. In the report, Riggs stated that his resignation was "perpetually before them." Riggs' resignation offer was declined.

-

President Riggs submitted a Special Report to the Board of Trustees following the walkout. In the report, Riggs stated that his resignation was "perpetually before them." Riggs' resignation offer was declined.

-

Letters from parents flooded in to President Riggs expressing dismay at the actions of the students. As in this letter, many parents implored for their student to be reinstated and argued that their student was purely motivated by peer pressure.

-

President Riggs received numerous correspondence from around the country following the walkout. In this notable correspondence, a supporter blames the walkout on "anarchism" and "Bolshevism."

-

President Riggs' initial report immediately following the walkout by the freshman and sophomore classes.

-

President Riggs' initial report immediately following the walkout by the freshman and sophomore classes.

-

A letter sent by President Riggs to parents notifying them of a "general holiday" in order to ease tensions from the walkout.

-

A portrait of Cadet Thomas Crosland from the 1922 edition of "Taps," the Clemson yearbook. In the days leading up to the 1920 student walkout, Crosland faced disciplinary action for allegedly shouting "Bolsheviki" on campus.

-

Companies of Clemson ROTC cadets march in formation on campus. Image displayed in the 1920 edition of "Taps," the school yearbook.