Overview

Clemson College had a predilection for student protest movements in the first quarter of the 20th century. Complaints over the demerits system and the quality of food in the mess hall were frequent fodder for student activism, and this activism took the form of walkouts in 1900, 1908, 1920, and 1924. This project concerns the latter two walkouts.

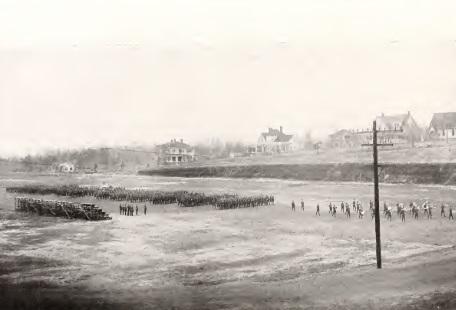

When the Morrill Act was introduced in 1862, it stipulated that land grant colleges must include "military tactics" in their curricula, and Clemson was no exception to this provision (Downs 168). The military component at Clemson was always a prominent feature, but military training was amplified after the United States entered World War I. When the National Defense Act of 1916 created the Reserve Officers' Training Corps (ROTC), land grant colleges like Clemson were the obvious choice of venue for more systematized military curriculum. Faced with the exigencies of World War I, however, the ROTC was not implemented in time to fulfill the need for trained troops. Therefore, in 1918 the Student Army Training Corps (SATC) was initiated, giving the War Department total control of accelerated military training at colleges. Schools across the country, including Clemson, "became veritable armed camps that trained soldiers and conducted an array of war-related activities" (Downs 177).

In the years following World War I, Clemson students--many of them veterans of the Great War--returned to a school that still operated within the vestiges of the SATC. The institution was rightfully proud of its military heritage and its commitment to the war effort, but disillusioned cadets complained about harsh disciplinary measures and subpar mess hall conditions. Furthermore, fear of the threat of communist revolution swept the nation during what came to be known as the First Red Scare. In the eyes of the general public, college students were among the groups most susceptible to communist ideas and revolutionary actions (Freeburg 3.) Indeed, there were instances of Clemson students acknowledging this working-class movement. The dynamics of the postwar years fostered a renewed sense of student activism, which culminated in the walkouts of 1920 and 1924. These two walkouts, especially that of 1920, led to structural change at Clemson, illustrating an increasingly democratically minded student body and a school administration that was willing to implement changes and improve the college experience at Clemson.