-Part 2-

Clemson Dependency upon Convicts

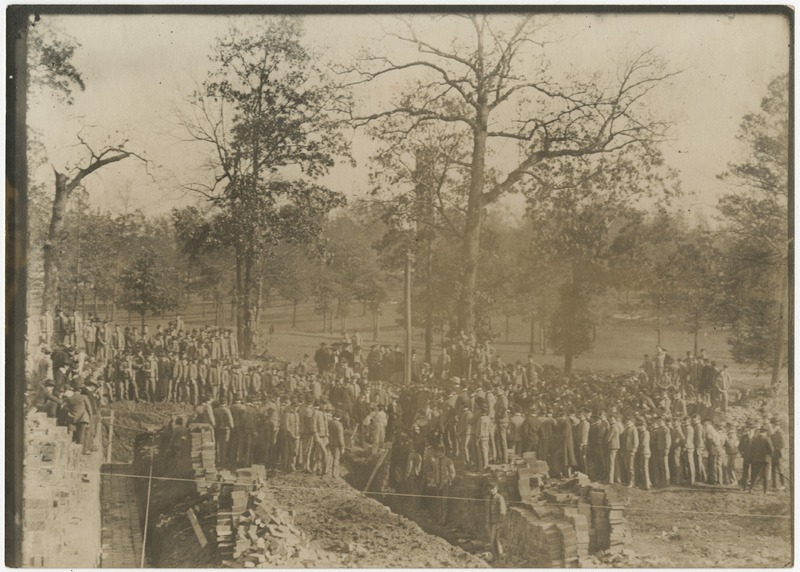

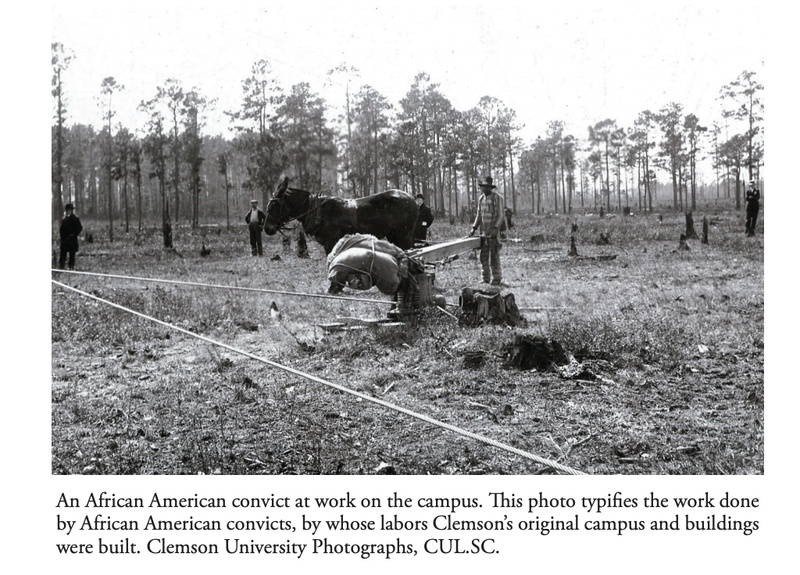

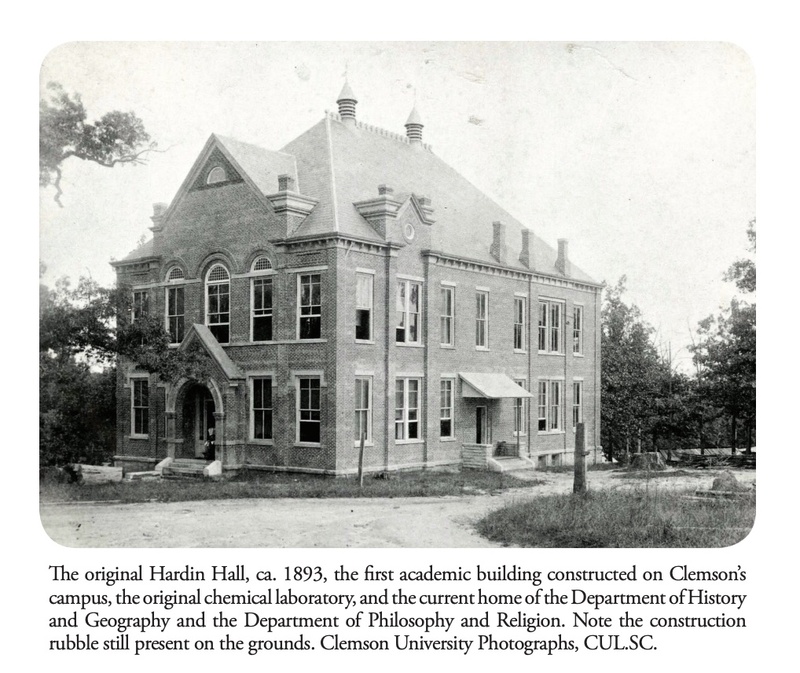

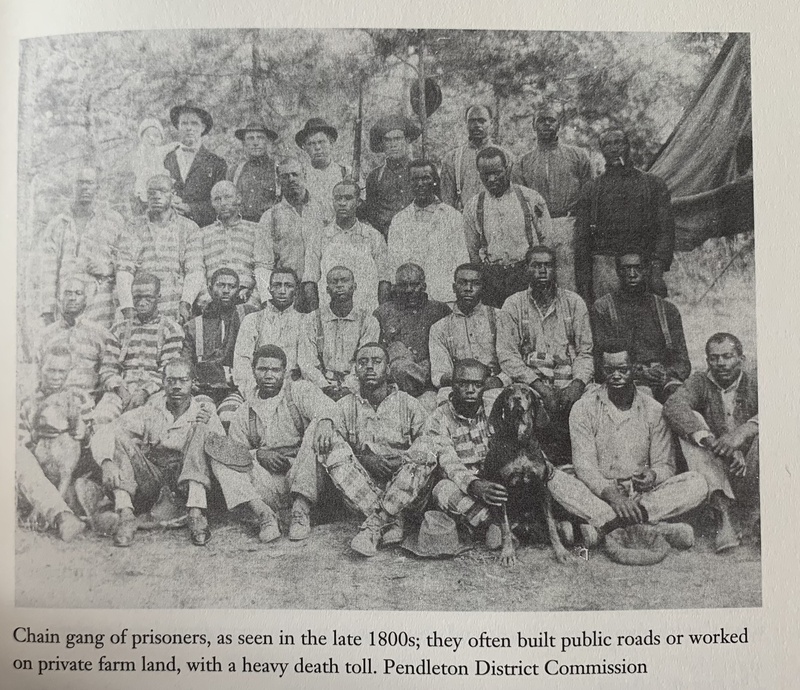

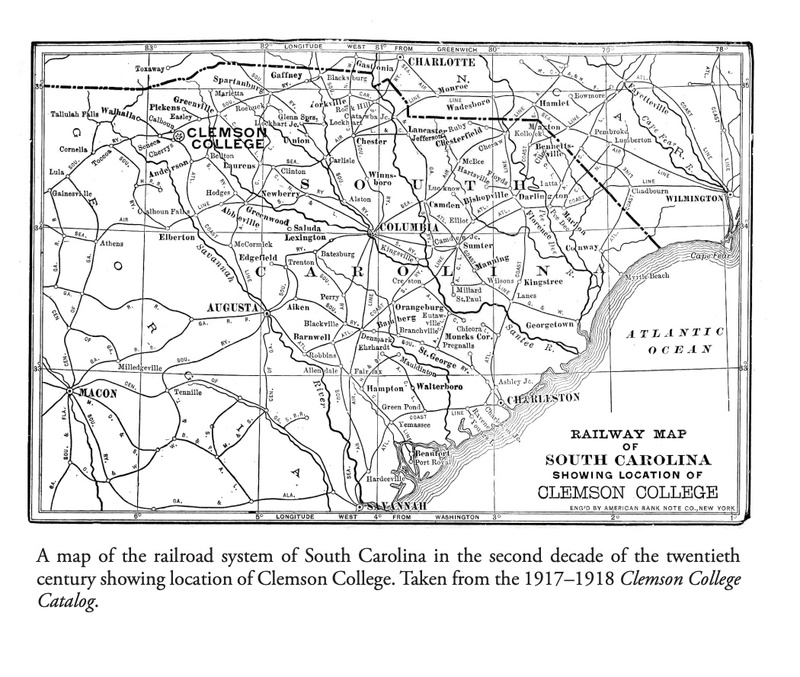

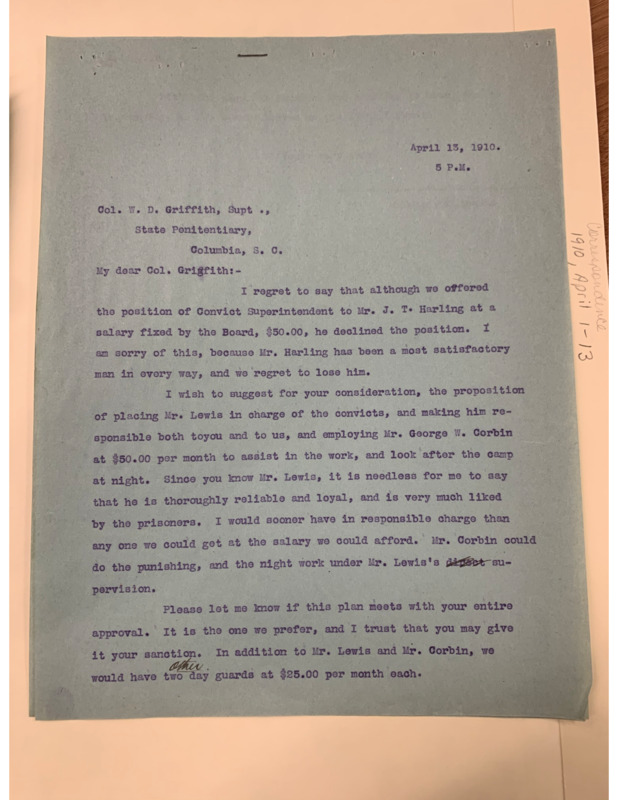

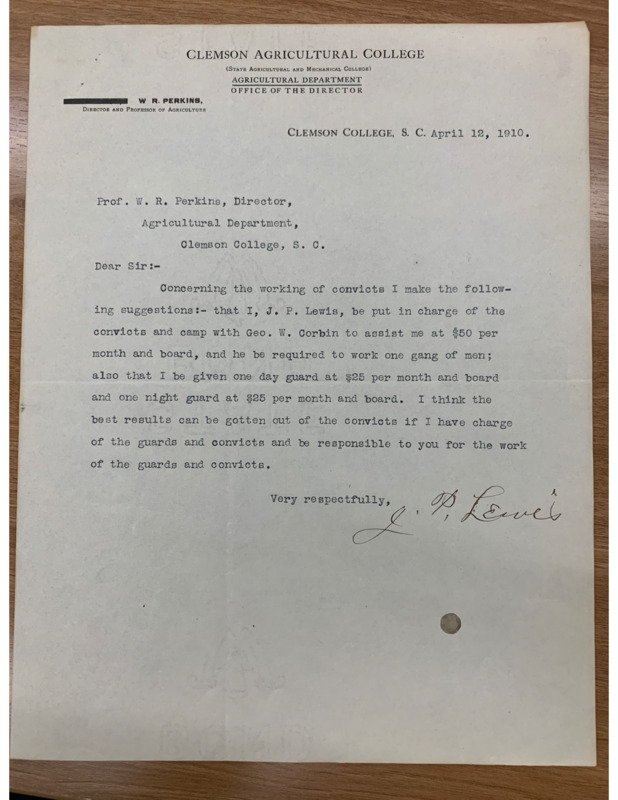

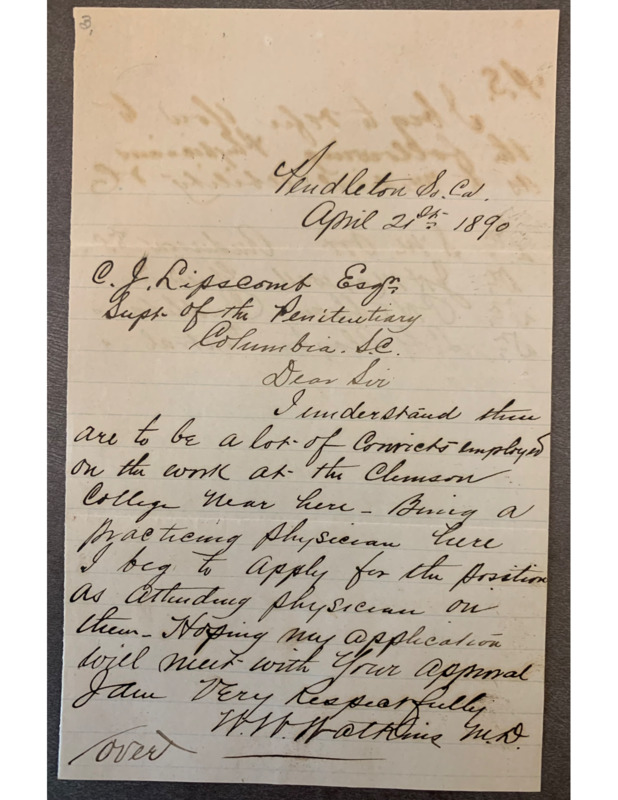

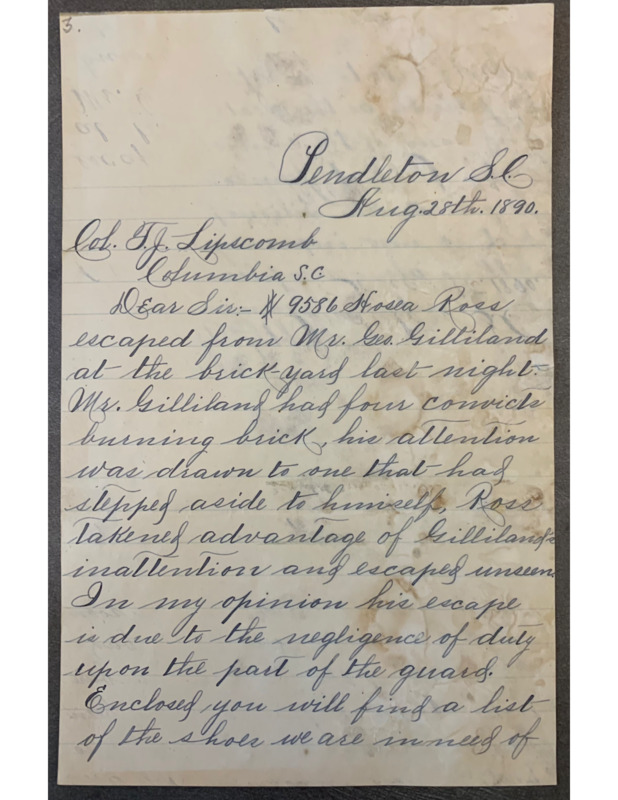

Clemson College was dependent upon the labor provided by black convicts of the state. As stated by Matthew Mancini, Clemson completed the first step for a successful convict labor system by aquiring the labor force necessary to build the college. Richard Wright Simpson, responsible for requesting the initial labor force, received a letter from the state penitentiary on January 23, 1891 explaining that sixty convicts were to be delivered. The letter also specified that the selection of convicts sent was made with the intention to meet the several demands of skilled labor, “…one carpenter, one…black smith, and…steel drivers,” were included within the convicts sent.[2]

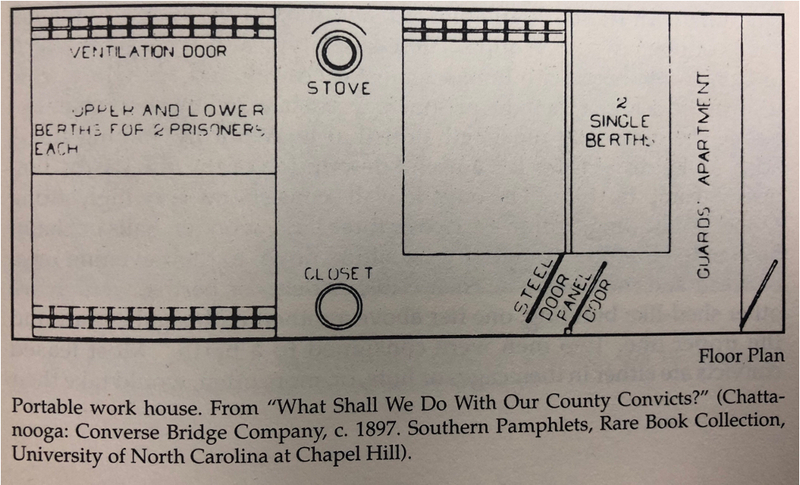

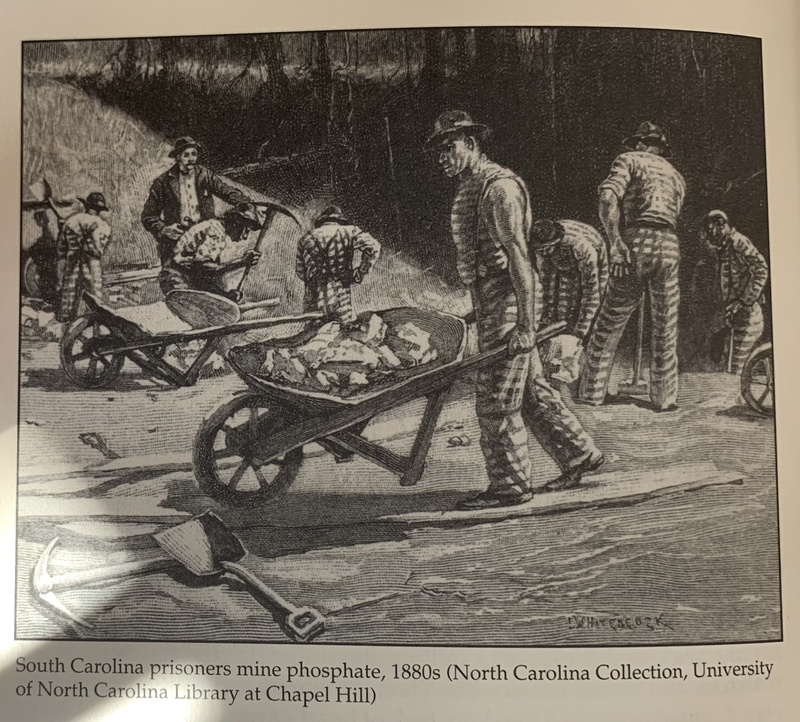

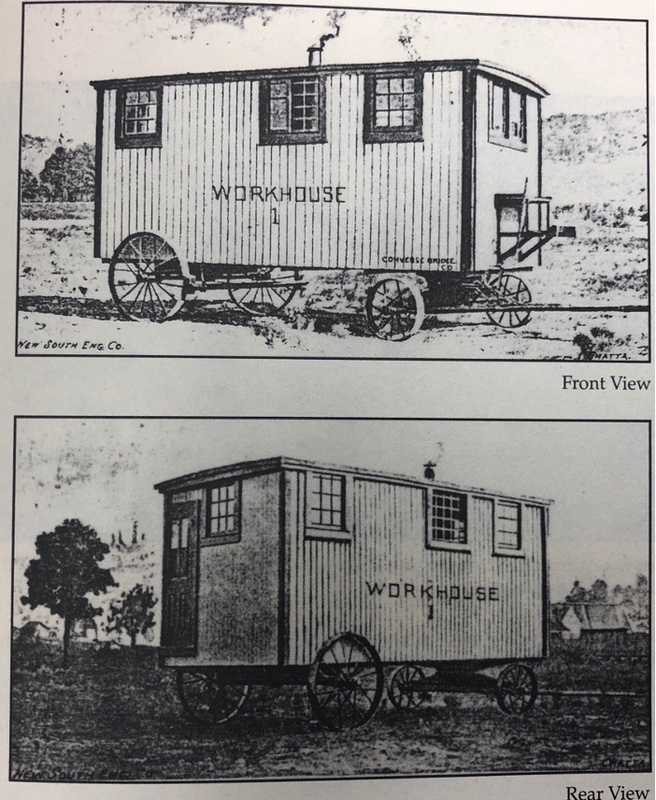

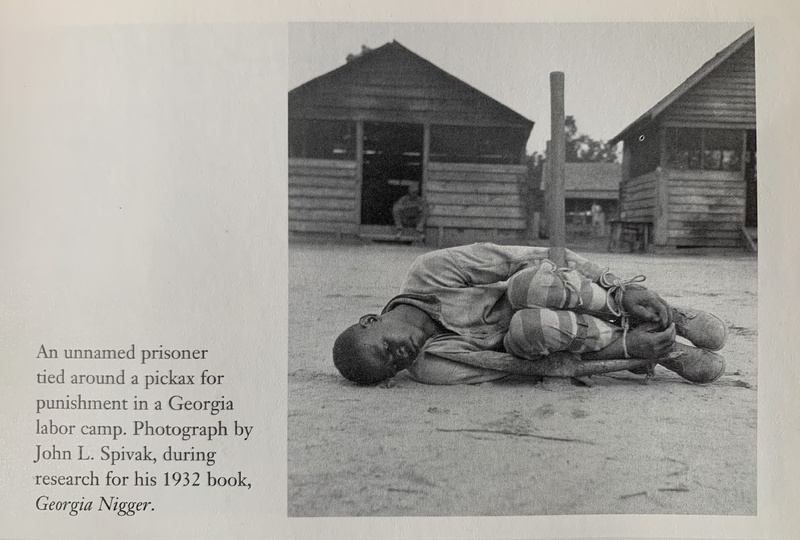

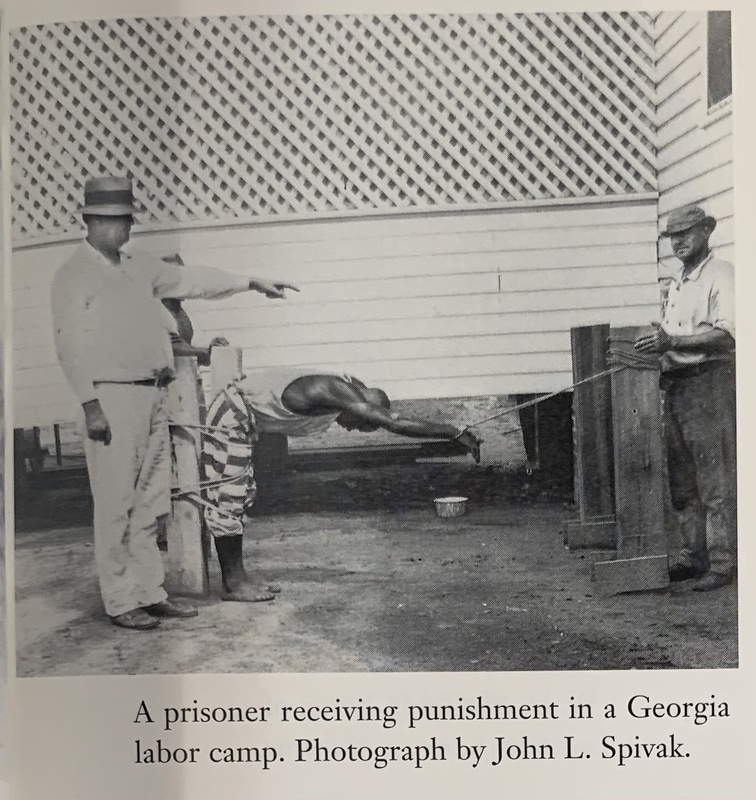

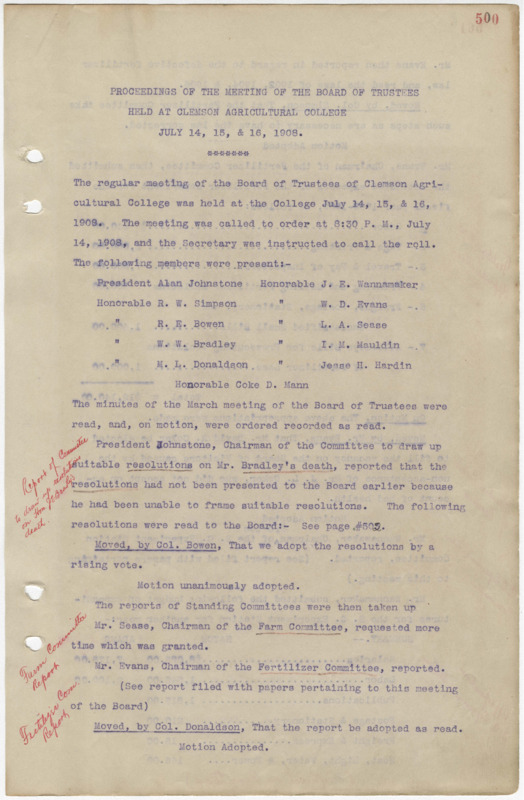

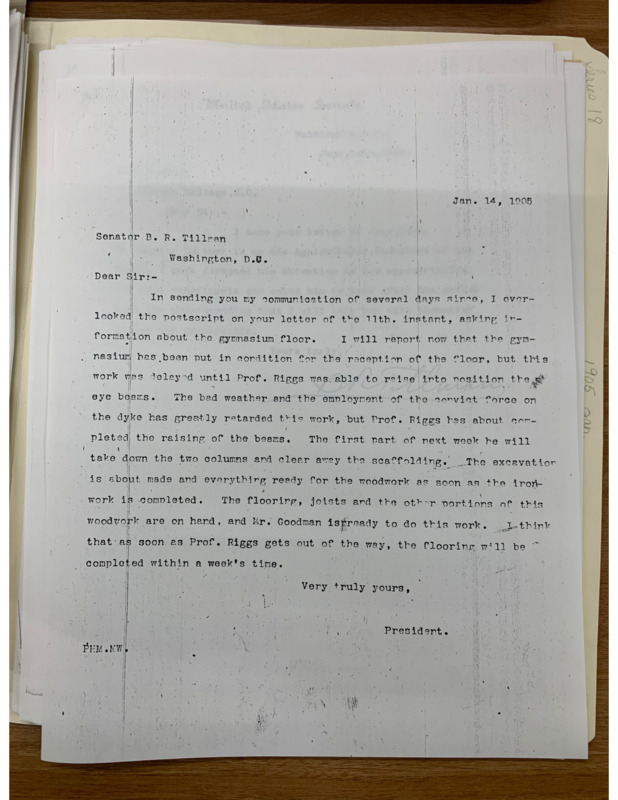

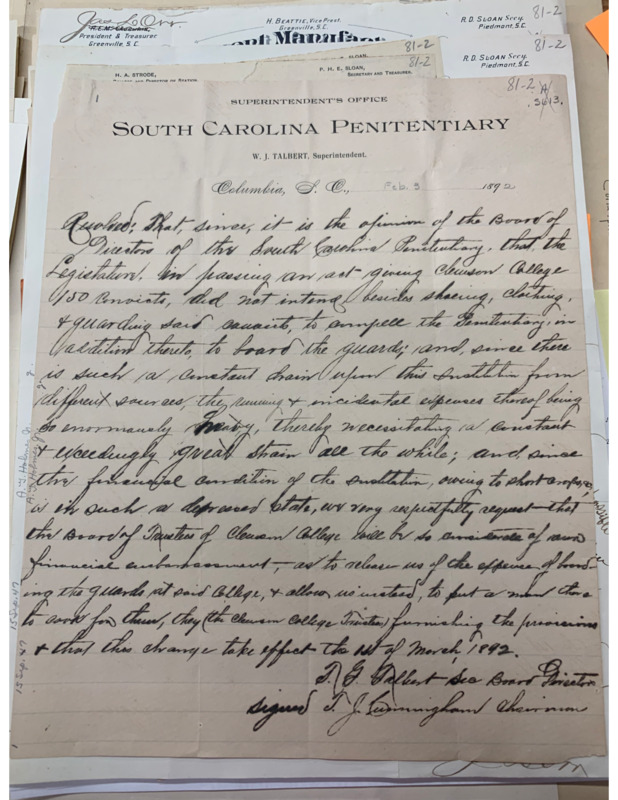

Convicts utilized by Clemson labored to construct the campus, complete agricultural tasks, and work on experiment stations. As seen in the Clemson Trustees Minutes, convicts were needed to complete tasks like, “…clearing the experiment station grounds.”[3] The toll that labor took on convicts was harsh, but keep in mind that “most of the inmates and their supervisors had plenty of practical farm experience, which meant they needed little to no training and each person knew or quickly understood their role.”[4]

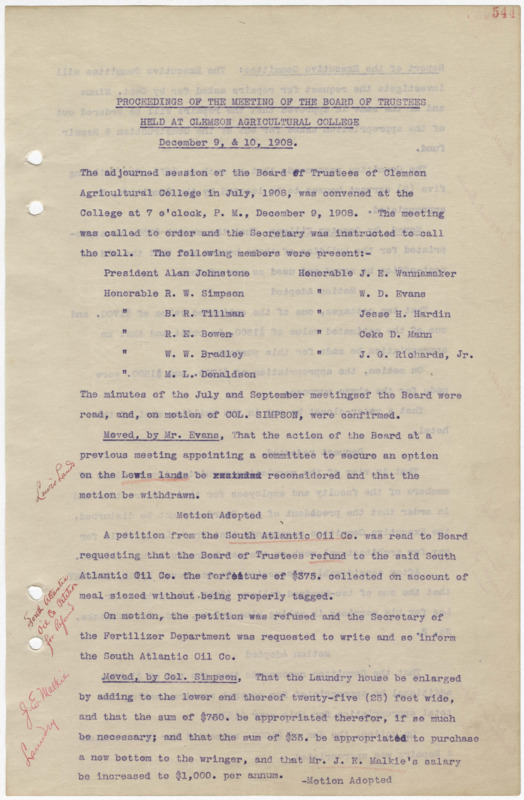

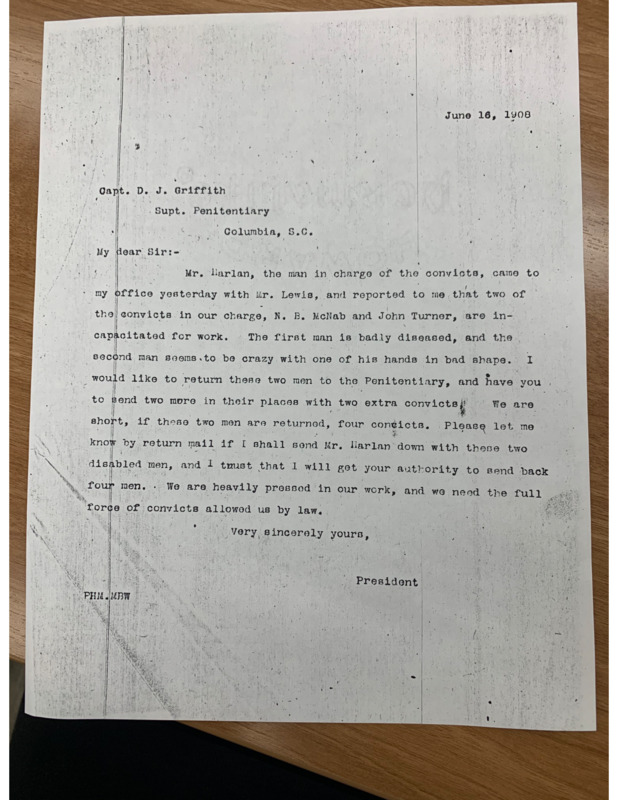

Convicts were used to bear the brunt of the labor necessary, but Clemson College took some precautionary measures to ensure the treatment of the convicts in their employ was marginally decent. For instance, the following motion was moved within the Clemson Trustees Minutes in December 1908: “That the dangerous things around the barn be moved and that the barn itself be made sanitary, and that a committee of the Board and the Foreman of the Farm look after this work, and that the convict, be required to bathe their hands and put on clean clothing before milking.”[5] In June 1908, a letter from Captain Griffith was sent to President Mell explaining the incapacity of two convicts to work. “The first man is badly diseased, and the second man seems to be crazy with one of his hands in bad shape.”[6]

Similar precautionary measures were taken to ensure that the convicts were being fed enough. In the March 1911 President’s Report to the Board of Trustees, the following was included, “We are selling the best of the table scraps to the convicts at $2.00 per day, in this way making a substantial saving to the College and giving the prisoners a better variety of food. The remainder of the slop is sold to the Farm at $2.00 per day, and payment taken in pork…”[7] Matthew Mancini offers more on how convicts were fed,

“…Most leased convicts ate…. endlessly repeated versions of the same basic pattern – beans, cornbread, molasses, and, in season, some vegetables – potatoes, turnips, beans – and even fruit. Meat was often included in an unappetizing stew that, convicts throughout the region complained, was often undercooked.”[8]

From these and other examples, answers to inquiries about how convicts were treated can be seen.

[1] Matthew J. Mancini, “Labor,” in One Dies, Get Another: Convict Leasing in the American South, 1866-1928 (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1996), 41.

[2] “Correspondence describing the convicts sent to Clemson,” Folder 15, Box 1, Richard W. Simpson Papers, Mss. 96, Special Collections Library, Clemson University Libraries, Clemson, S.C.

[3]Clemson University Board of Trustees, "Clemson Trustees Minutes, 1908 July 14-16" (1908). Minutes. 357. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/trustees_minutes/357.

[4] Andrew James Sean Duncan, “Honorable and Successful Convict Leasing in South Carolina, 1877-1902.” PhD diss. (Columbia: University of South Carolina, 2004), 46.

[5] Clemson University Board of Trustees, "Clemson Trustees Minutes, 1908 December 9-10" (1908), Minutes, 371, https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/trustees_minutes/371.

[6] Convicts Incapacitated for Work, Folder 64, Box 3, Patrick H. Mell Presidential Records, Series 18, Special Collections Library, Clemson University Libraries, Clemson, S.C.

[7] Clemson University, "President's Report to Board of Trustees, 1911-03" (1911), President's Reports to the Board of Trustees, 131, https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/pres_reports/131.

[8] Matthew J. Mancini, “Camps,” in One Dies, Get Another: Convict Leasing in the American South, 1866-1928 (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1996), 62-64.