Restoration 1931-1941

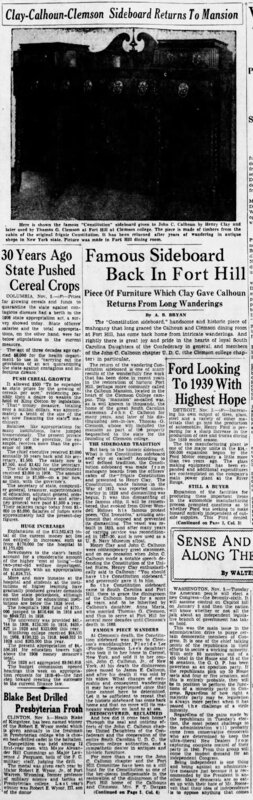

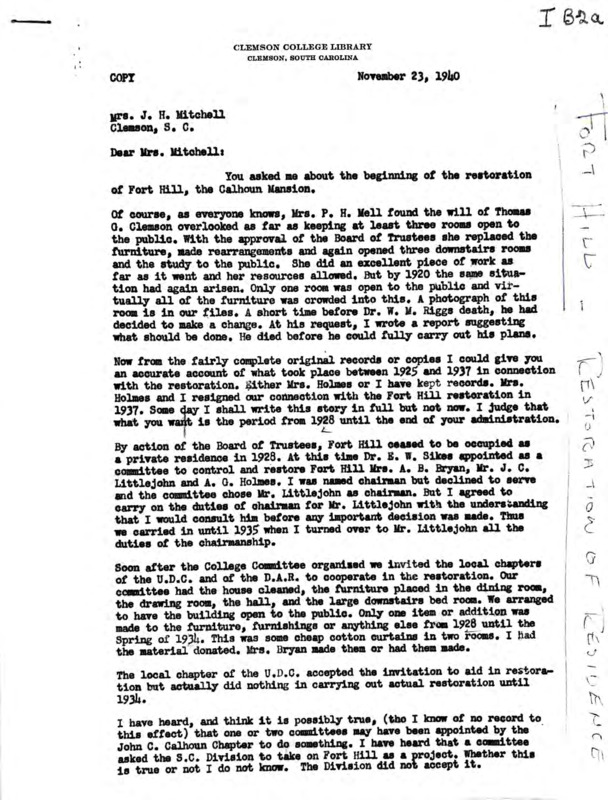

On March 11, 1931, The Tiger Newspaper heralded in a headline above the fold of the newspaper “Old Calhoun Mansion Opened as Shrine: Plans Being Made to Restore Grounds to Original Beauty.” (Old Calhoun Mansion Opened as Shrine 1931). As if a starter pistol had been shot, the restoration was underway. People, politics and preservaton would define the decade. In the midst of the Great Depression, prototypical preservationionist composed of representatives of various patriotic organizations, particularly the United Daughters of the Confederacy, first with the local John C. Calhoun Chapter and later with the State Division would collaborate and sometimes clash with professors, administrations, and University presidents.

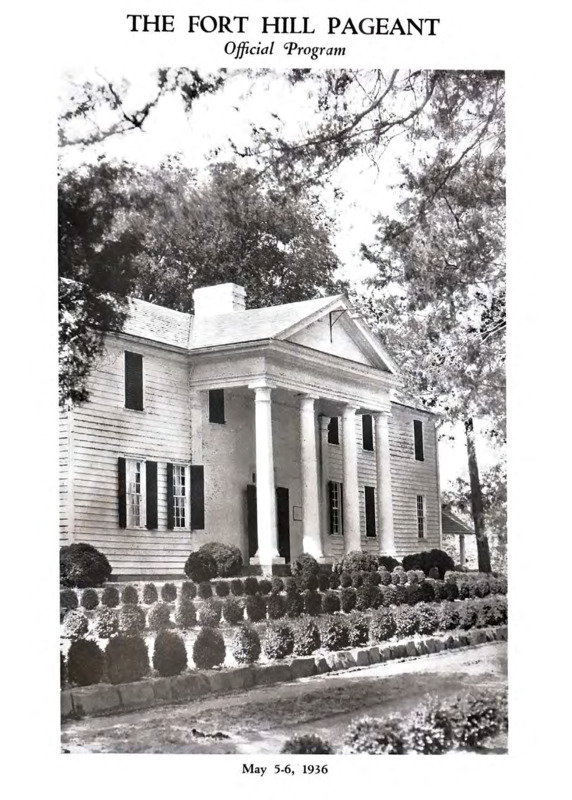

One keystone event of the 1930s activities was a The Fort Hill Pageant held on the football field May 5-6, 1936, (today known as the soccer stadium or Riggs Field). The event included a cast of thousands, or at least several hundred and was presented two days. The outdoor drama program provided a showcase experience reminiscent of the "Lost Colony" in Manteo or "Unto These Hills" in Cherokee, N.C. A professional pageant firm Harrington-Russell was contracted with from Ashville, N.C. who provided technical assistance, costuming, reviewed scrips, and promoted the event.

Ironically, the financial outlay by the committee and the college was not even break even, but a loss. However, from a visibility and public relations standpoint the case could be made that the event had been successful. However, the portrayals of historical events were characteristic of its era in relation to Native-American and African American

representations. That the pageant featured a minstrel segment in black face would seem unfathomable, yet it took place.

What is in a name Fort Hill or Calhoun Mansion? That was the question that boiled to the forefront during the mid-1930s. The year 1936 signaled an emerging conflict revolving around the nomenclature which is as central to the heart of the issue of its mission as a museum. It is also significant understanding of what the historic site would be. A newspaper article in the Greenville News on March 25, 1938, was entitled, “Mansion Is Disputed: Fort Hill Is Former Calhoun Home and Not His “Mansion.”

To understand the context, the disagreement revolving around the name has all the intrigue of people, politics, and preservation. On one side of the issue was Professor Alester Holmes and his wife Lila Holmes who had tirelessly worked toward the restoration of Fort Hill. History Professor Alestor G. Holmes along with Dr. George. Sherrill had just published a book length biography entitled Thomas G. Clemson: His Life and Work in 1937. As often is the case in conflicts over politics, the value of logic pails under agendas. As theFort Hill: John C. Calhoun Shrine booklet would later detail, “The UDC and Fort Hill have much in common as it was the home of four Confederate soldiers: John C. Calhoun, III, Duff G. Calhoun, John Calhoun Clemson, and his father Thomas G. Clemson”. The issue of what is in a name continued.

Taken in that context, the UDC had a foothold with Fort Hill in a memorial to the “Lost Cause” that would be much more expansive than a simple statue on a county courthouse square. At Fort Hill, the invitation to participate in the restoration of Fort Hill at a College Campus stipulating the ancestry of its curator as southerner and a member of the UDC or eligible was simply put a coupe.

In 1938, Jane Prince, the 89-year-old former housekeeper for Thomas Clemson was interviewed and was one significant source of oral history of Fort Hill and Mr. Clemson. The restoration of Fort Hill’s exterior kitchen was based upon her eyewitness accounts transcribed by J.C. Littlejohn.

The advisory committee charged to restore Fort Hill interviewed Thomas G. Clemson’s housekeeper to Thomas Clemson’s last years at Fort Hill. A newspaper article in the Tiger, was entitled “Former Fort Hill Housekeeper Cherishes Relics Left Her by Thomas G. Clemson.” Jane Prince was at that time 89 years old and related fond memories of the founder. Interestingly both she and her daughter Essie Prince (Boggs) were provided for in Thomas G. Clemson’s Last Will & Testament. Both mother and daughter lived in Fort Hill and were a surrogate family in his waning years.

In February of 1938, Architecture Professor Rudolph E. Lee announced that working with a team of architecture student, they had discovered the stone foundations “believed to be the remains of the old slave quarters.” As to what became of the walls of the enslaved stone dwellings, the best clue is a footnote in John C. Calhoun: The Man that stated that, “the ultra-modern Architectural and Engineering building of Clemson University occupy the site of the plantation slave quarters, when the house were demolished many of the stones in them were utilized in some of the Institution’s early buildings.” The article by R. C. Forsythe, “Architects Locate Sites of Mansion Buildings” stated that their goal was to the creation of “A plot plan showing these sites will be made by the students, and it is hoped that the collect will place markers at the various sites, thus preserving to posterity historical data which up to how has been lost.”