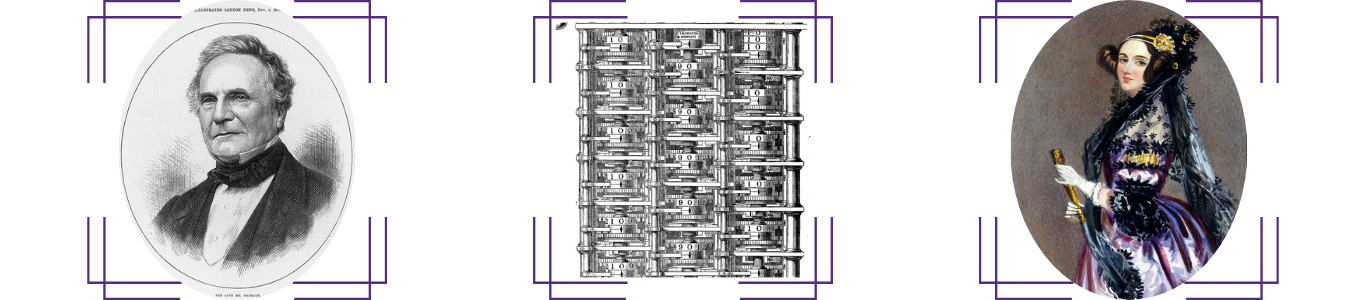

Nearly 70 years before the formation of Clemson College, British mathematician and economist Charles Babbage recognized a problem. Various mathematical tables, such as algorithmic tables, were often used in nautical navigation, but errors lead to an array of problems. Around 1820, Babbage sought to eliminate errors in these tables. Drawing inspiration from industrialized factory machinery, Babbage attempted to invent a machine which would not only compute the mathematical polynomials but also print its results. His so-called Difference Engine (sometimes called the Difference Machine) was based on a mathematical principle known as the finite difference method, which allows one to solve differential equations by approximation rather than exact calculations. This method allowed Babbage to only utilize addition in his machine, making it much simpler to mechanize than if more complex operations such as multiplication or division were involved. Babbage’s plans for the Difference Engine were incredibly detailed, and the most complex version of the machine called for about 25,000 parts, would have stood eight feet high, and was estimated to weigh four tons if completed. Between 1991-2002 a complete machine faithfully constructed from Babbage’s original designs was constructed by the London Science Museum.

In 1834, Babbage began work on another computational machine which he called the Analytical Engine. Where the Difference Machine had strictly been a calculation machine, the Analytical Engine was a programmable computer, able to run numerous functions depending on the punch card the operator supplied. Ada Byron Lovelace’s writings about the theoretical Analytical Engine included a description of an algorithm that would allow the Analytical Engine to compute Bernoulli numbers, which is now widely considered to be the first published computer program; Lovelace is often referred to as the first computer programmer for this reason.