Much has been written about the gender disparity in the STEM fields, including in Computer Science. A 2019 New York Times Magazine feature article, “The Secret History of Women in Coding,” discusses the issue in detail, explaining that in the early days of software development, the field employed fairly even numbers of women and men. However, in the mid-1980s a drastic change in these numbers occurred. Rather than the amount of women in the field continuing to grow as it had over the last 10-20 years, it began to decline. And it kept declining. Today, only about 20% of computer science graduates are women. Using Clemson Computer Science faculty interviews, previous research about the field as a whole, and the history of southern public coeducation, one can begin to understand the issue of women in computing at Clemson University.

At Clemson, this issue seems to be remembered differently among faculty members. Dr. Mike Westall came to Clemson as a Mathematics professor in 1974, when computer science courses were offered as an option of the Mathematics undergraduate degree. Westall reports that in the early days of Clemson’s Computer Science courses the ratio of male to female students was nearly equal, explaining that, “In a class of 35 students in 1978, you might have twenty men and fifteen women.” Then, around 1985 or so, those numbers shifted dramatically. Westall says that suddenly in that same undergrad course, there might be something like “32 men and three women.” However, Dr. Joe Turner, who came to Clemson’s Math department in 1975 and would eventually serve as the Department of Computer Science’s first director, remembers things a bit differently. According to Turner, he doesn’t remember there ever being a “reasonable number” of female students in Computer Science courses. Dr. EIeanor Hare, also a member of the Computer Science faculty and who would eventually be the first woman to earn a Computer Science PhD from Clemson, similarly remembers very low enrollment of female students throughout her time at Clemson. It is difficult to say which account is most accurate, as gender specific Clemson course enrollment data is not available prior to August 1999. Additionally, a Self-Study Report issued by the department in 1980 (and a broader report issued by the College of Sciences in 1981) does not mention any student demographic information.

Both Westall and Hare attributed the low number of women in the program at least in part to female students being hesitant to seem “nerdy” or be associated with “nerds.” Westall named the film Revenge of the Nerds (1984) in particular– in which the geeky protagonists install hidden cameras in the women’s dorm rooms and showers. Revenge was presented alongside Sixteen Candles (1984), in which the token nerd collects tickets to show off Molly Ringwald’s panties, and Weird Science (1985), in which two nerdy teens create a woman and proceed to ogle her for 90 minutes. As media representations of young men who were interested in math and science painted them as perverted and socially inept, it’s perhaps understandable that young women in the 1980s were hesitant to associate themselves with “nerds.” The authors of “Computing Whether She Belongs: Stereotypes Undermine Girls’ Interest and Sense of Belonging in Computer Science” explain that stereotypes such as the ones presented in the films listed here are a factor in high-school aged girls’ decision to forego computer science and other STEM fields, which in turn impacts the number of young women who enroll in college level computer science courses.

While Westall’s account speaks to the mid-1980s drop in women in the field, Hare and Turner report low numbers of women in the program throughout. Hare speaks on this issue in her oral history interview around 18:30-23:00, explaining that computing at universities in the 1960s and 1970s was most often a product of other departments, such as Mathematics or Physics. As such, it was students in those departments who were most likely to interact with computers— and, she explains, those students were overwhelmingly male. Women, if allowed to enroll in southern universities at all, were expected to go into traditionally feminine fields such as nursing, education, or secretarial work.

This was not an accident. Southern, state-funded colleges and universities fought fervently against coeducation in the early 20th century. In South Carolina, late 19th-century and early 20th-century efforts to make a state college coeducational have been read as a political attack. As Amy Thompson McCandless explains in “Maintaining the Spirit and Tone of Robust Manliness: The Battle against Coeducation at Southern Colleges and Universities, 1890-1940,” South Carolina Governor Ben Tillman was met with public outcry when he suggested making South Carolina College (now the University of South Carolina) coed in 1893. McCandless argues that Tillman’s (ultimately successful, despite several caveats) attempt to make South Carolina College coeducational were not rooted in any kind of feminist belief. Rather, it is likely that the governor, who politically opposed “the continued dominance of the cultured aristocrats of the low country,” sought to “’punish’ those men who wished to maintain the social exclusivity of the university.” South Carolina College was a rather elite space, providing a classical education which would prepare white men for careers in law and government; making it coeducational would have been seen as lessening this elite status. This argument is supported by the Tillman administration's 1891 establishment of the Winthrop Normal and Industrial College of South Carolina which offered courses (for women) in education, dressmaking, and home economics and its 1893 establishment of Clemson College, which focused on agricultural and military pursuits (for male students). Even as these new schools were being established, no conversation regarding coeducation occurred. Tillman fought for coeducation in Columbia as a way to lessen the hold of the elite in the state. The male faculty and students (and the public) were nearly unanimously against the change.

While efforts toward public coeducation in other southern states were likely not as politically pointed as those in South Carolina, they were met with similar disdain. When women were allowed to attend classes on the main campus, they often found that no women’s dormitories were offered; they instead would need to live close enough to commute daily or find other nearby housing— this would eventually be the case at Clemson. The fight for southern state-funded coeducational institutions continued well into the mid-20th century and beyond. Indeed, The Citadel (a public military institution in Charleston, SC) engaged in a two year legal battle with Shannon Faulkner when she attempted to enroll in 1993; Faulkner won her case, but 20 years later women still only account for 13% of the undergraduate population.

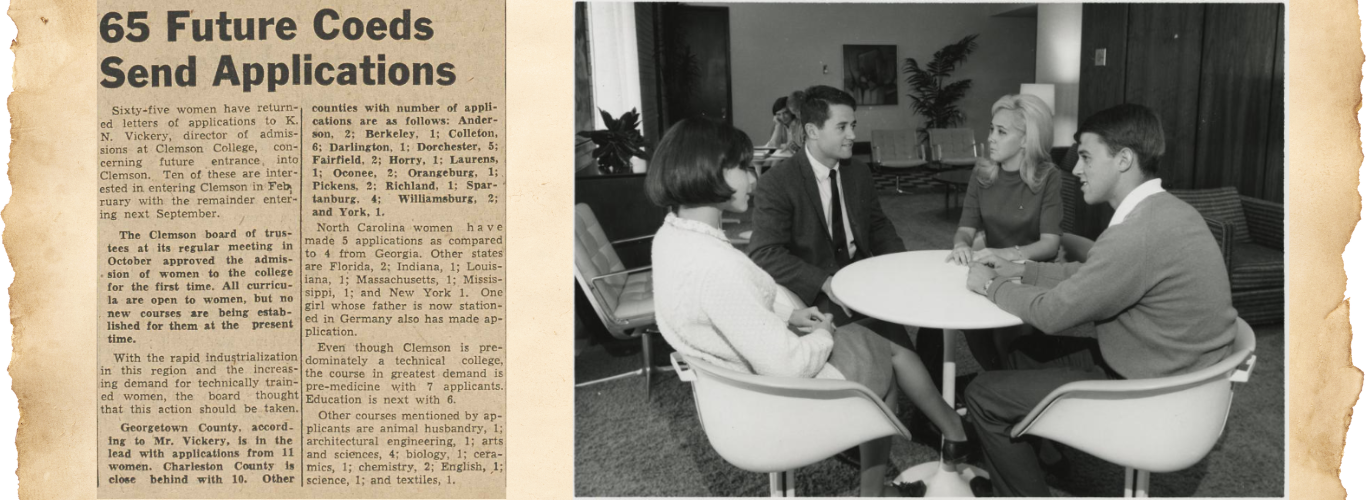

Clemson College officially welcomed white women as undergraduate students in January 1955. Again, this decision was not made for the ideals of feminism or equality, but because Clemson’s enrollment post-WWII was dropping rather significantly. To combat low enrollment numbers, President Robert Poole allowed degree-seeking undergraduate female students to attend the school, provided they had living accommodations off-campus such as parental homes or all-women boarding houses; the first women’s dormitory was not opened until fall 1963.

Women who attended Clemson in the early years of going coed reported mixed reactions from male students and faculty. For example, Mary Ellen Summey Warner is quoted in Women and Clemson University: Excellence Yesterday and Today saying that she was barred from a math class due to the professor’s sexism, but that other professors welcomed her and spoke up for her. Women were also held to more strict rules of conduct than their male counterparts, especially after introducing the dormitory in 1963. Dress codes (inside the dorm, in classrooms, and around campus), curfews, and “in-and-out” cards were utilized for female students until the mid-1970s. Though there was no official ban of certain programs for female students (indeed, the first woman to graduate with a bachelor’s degree from Clemson studied Chemistry), an alumna reported being discouraged from enrolling in a science program and pushed into a more traditionally feminine major such as Education as late as 1973.

With this history of southern coeducation in mind, it is perhaps not surprising that Dr. Turner and Dr. Hare report always seeing incredibly low numbers of women in their Computer Science courses. The earliest available gender specific data for general Clemson enrollment comes from 1970. By that time, about 22.5% of Clemson’s undergraduates were women. In 1978, the percentage of women increased to about 40%. So, if female students were equally dispersed among academic majors (which is unlikely), a 1978 Computer Science class of 35 students should have contained around 14 women. These are the numbers Dr. Westall reported, before he says they decreased dramatically in the mid-1980s. Dr. Hare was surprised even by Westall’s drop-off number, saying she was shocked he even had one or two female students in a course at any time. As the data does not exist and we must rely on individuals’ memories which are obviously at odds with each other, we simply do not know the number of women who participated in Clemson’s Computer Science program prior to the Fall 1999 semester. At that time, women accounted for 37% of the undergraduate Computer Science program and nearly 46% of the overall undergraduate population.; in 2022, despite female students representing 51% of the undergraduate population, the percentage of women in Computer Science had fallen to 17%. While these numbers may seem damning to Clemson in particular, a 2022 Scientific American article reported that “only 20 percent of computer science and 22 percent of engineering undergraduate degrees in the U.S. go to women.”

A 2016 Journal of Educational Psychology article sought to explain why these numbers continue to be so low. The authors identified computer science as having the “lowest percentages of women among science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) fields” and argued that because “gender differences in high school achievement in STEM do not explain the gender gaps in college enrollment,... nonacademic factors that influence girls’ academic choices” should be researched. They proved that stereotypical views held about the field of computer science work to “deter adolescent girls from pursuing introductory computer science courses.” The stereotypes in question included the belief that computer scientists are overwhelmingly “male, technologically oriented, and socially awkward,” and that computer science requires “‘brilliance,’ and is isolating and does not involve communal goals such as helping or working with others.” The authors argued that both previously held stereotypes and objects in the physical environment (ie the computer science classroom) work to make young girls feel they do not belong in the environment. From the study, “The stereotypical objects were Star Wars/Star Trek items, electronics, software, tech magazines, computer parts, video games, computer books, and science fiction books. The nonstereotypical objects were nature pictures, art pictures, water bottles, pens, a coffee maker, lamps, general magazines, and plants.” The authors found that while the number of high school girls interested in taking an introductory computer science course increased significantly when shown the classroom containing nonstereotypical items, high school boys’ interest did not increase or decrease between either classroom; thus, creating nonstereotypical environments in high school computer science classrooms would draw more female students without deterring male students. As a result, more young women would continue into college-level computer science programs.

Women in computer science (at Clemson and elsewhere) is obviously a complex issue with many contributing factors. Historically, women have not been incredibly welcome in academic spaces (especially scientific spaces); this was an issue at southern institutions well into the mid-20th century. Women’s relatively late start (outliers notwithstanding) into the sciences in general bled into their low numbers in computing. While the number of women in the field did start to grow in the 1960s (see “The Secret History of Women in Coding”), clearly something happened to stifle this growth in the 1980s. Given media representations of “computer nerds” and Master et. al.’s research on stereotypes affecting adolescent girls’ choices to pursue STEM, this change seems to be reflective of the culture in general (which Hare speaks to in her oral interview) rather than an implication of any particular institution.

References

Cheryan, Sapna, Allison Master, and Andrew Meltzoff. 2022. “There Are Too Few Women in Computer Science and Engineering.” Scientific American. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/there-are-too-few-women-in-computer-science-and-engineering/.

Clemson University College of Sciences. 1981. College of Sciences Self Study 1981, Archival material. Clemson, South Carolina: Office of Institutional Research.

Clemson University Department of Computer Science. 1980. Self Study Report, Archival material. Clemson, South Carolina: Office of Institutional Research.

Master, Allison, Sabna Cheryan, and Andrew Meltzoff. 2016. “Computing Whether She Belongs: Stereotypes Undermine Girls’ Interest and Sense of Belonging in Computer Science.” Journal of Educational Psychology 108, no. 3 (April): 424-437.

McCandless, Amy T. 1990. “Maintaining the Spirit and Tone of Robust Manliness: The Battle against Coeducation at Southern Colleges and Universities, 1890-1940.” The National Women's Studies Association Journal 2, no. 2 (Spring): 199-216. https://www.jstor.org/stable/4316017.

Reel, Jerome V. 2006. Women and Clemson University: Excellence--Yesterday and Today. Edited by Alma Bennett. Clemson, South Carolina: Clemson University Digital Press.

Thompson, Clive. 2019. “The Secret History of Women in Coding.” The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/02/13/magazine/women-coding-computer-programming.html.